Editing: Georgia Nakou

While the world of football is slowly coming around to LGBTQ+ issues, homophobic behaviour is routinely tolerated among Greek teams, management and fans. Even discussing homophobia is taboo, as our investigation found.

In recent years the governing bodies in football – such as UEFA and FIFA – have been trying to make football more open to LGBTQ+ issues. It’s encouraging that they have recognised the issue of homophobia in football, and they are making efforts to tackle it. After all, the first step is to identify the problem and not sweep it under the carpet. In Greece, things are still pretty different.

Homophobia? What is this?

“Every time I suggested to the governing bodies that they do something about homophobia, there was denial. I could see it in their faces, the faces of people who hold high positions. They were telling me with their eyes to avoid touching the issue,” says Antonis Daloukas, a former referee and representative of FARE, football’s anti-discrimination network, in Greece.

The first time Daloukas touched the issue was about ten years ago, when he approached the Superleague, the organising authority of the two highest football tiers in Greece, to create a campaign on the issue. When he faced denial around the issue, Daloukas backed off.

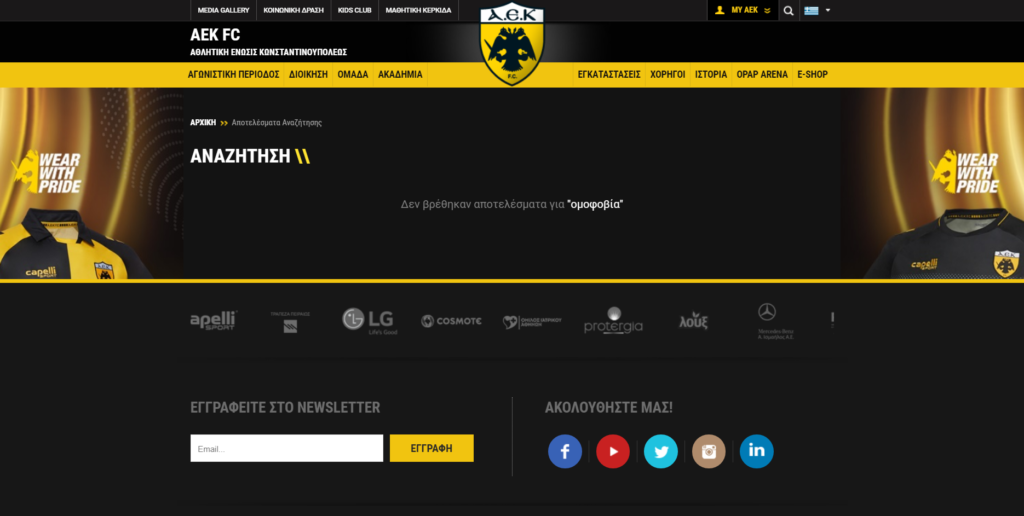

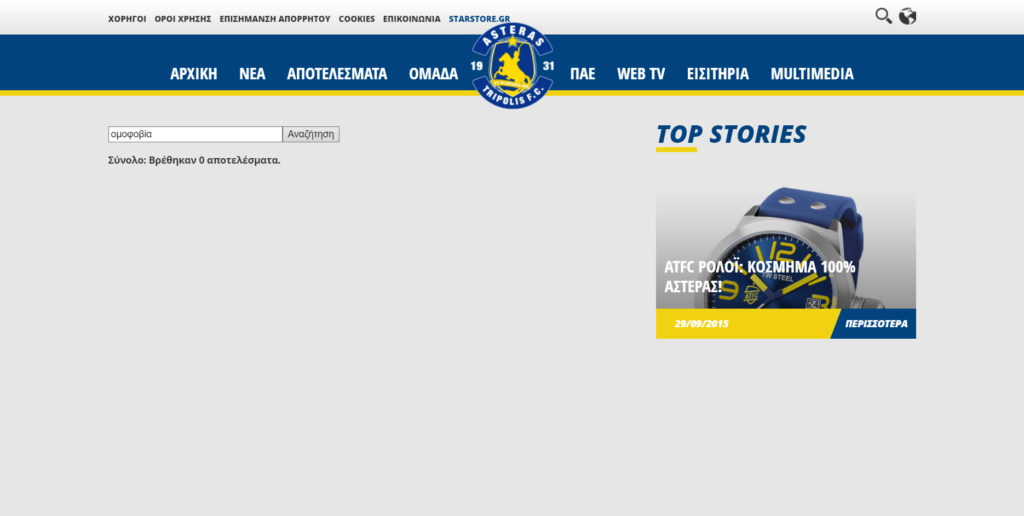

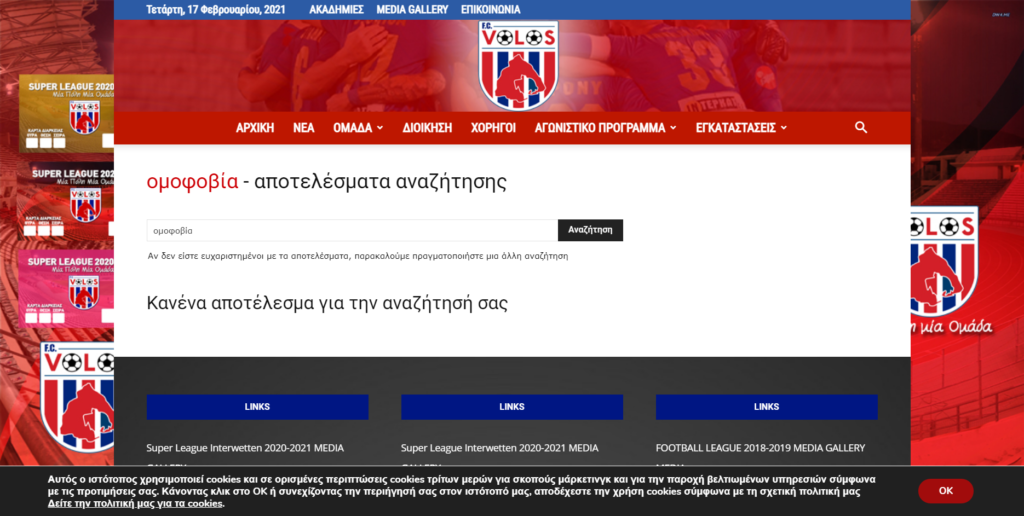

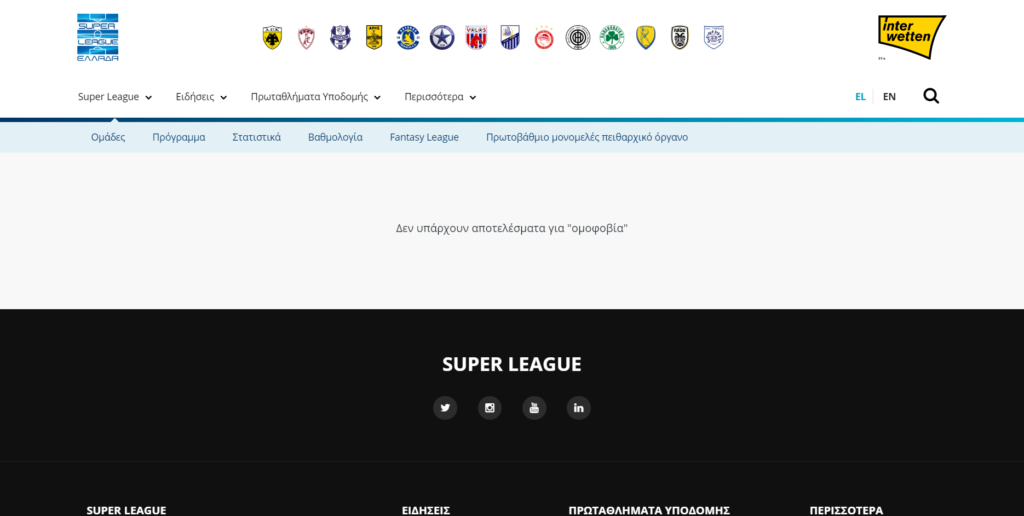

A decade later, the word “homophobia” has been ignored by almost every team participating in the Superleague, the Superleague as an organising authority, and the Greek Football Association (Greek FA). The word is not just ignored as a campaign issue but also not acknowledged as a term. It is simply a non-issue. If someone searches for the term “homophobia” in the websites of the 16 teams participating in this year’s Superleague they will find nothing. The same applies to Superleague’s website and also Greek FA’s website.

“No results for “homophobia”. Screenshots from the Superleague teams and the football governing bodies websites.

In the course of our investigation, Reporters United contacted the 16 Superleague teams, Superleague, and the Greek FA, about the issue. At the time of publication we have only received responses from Asteras Tripolis, PAOK, AEL, OFI, and the Superleague. The rest – including the big three, Olympiakos, Panathinaikos, and AEK – have ignored our emails.

“Inadvertently”

Reporters United also contacted the Panhellenic Association of Paid Football Players and its president, Giorgos Bantis, on two occasions; however, there was no reply. There was also no response to our effort to contact the newly elected president of the Greek FA and captain of the Euro 2004-winning national squad and Player of the Tournament, Theodoros Zagorakis, who – as a serving MEP with Greece’s ruling New Democracy party – had voted against LGBTQ+ rights. After the outrage in social media, Mr Zagorakis stated that he voted against “inadvertently” and later voted for LGBTQ+ rights, but he did not respond to our approach.

Lastly, Reporters United contacted some of the most prominent Greek fan clubs – such as AEK’s Original and Panathinaikos’ Gate 13 – but there was no reply.

The same deafening silence from the football world accompanied Athens Pride, with few exceptions.

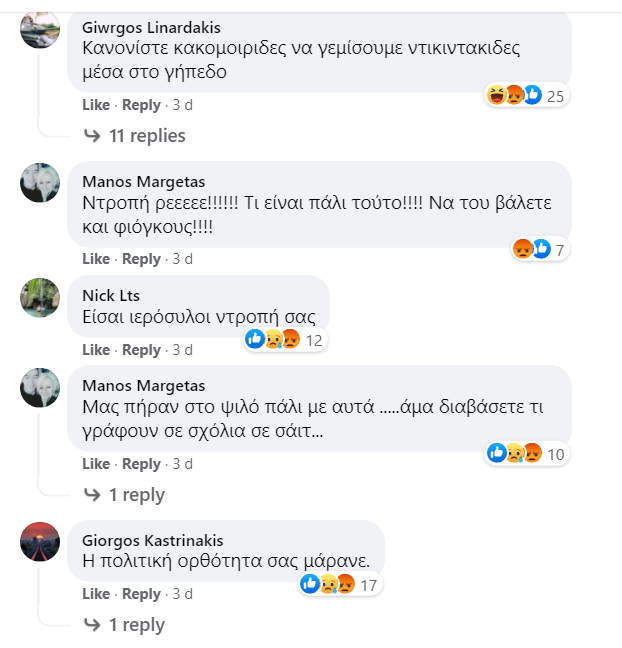

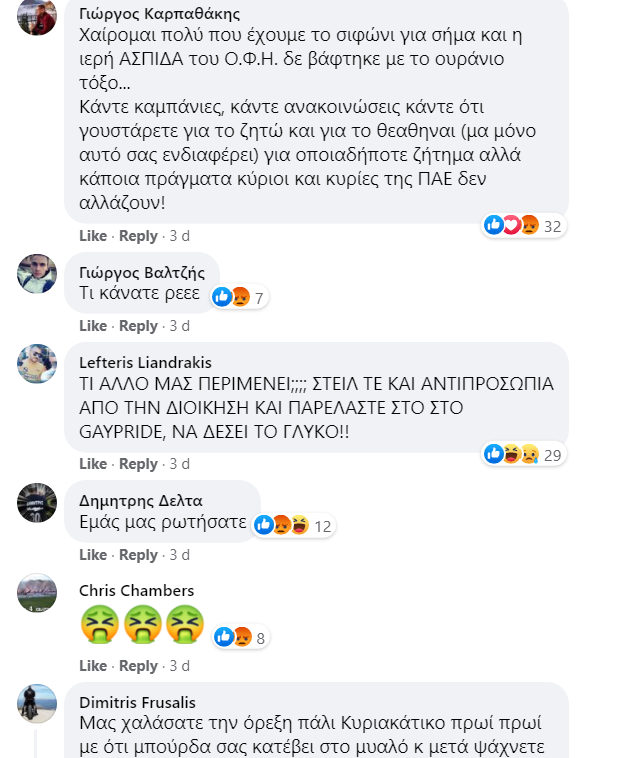

During Pride month, Cretan team OFI FC briefly changed its black-and-white crest colours to a rainbow to show its support to the LGBTQ+ community through social media. OFI became the first Superleague team to do this. However, two days later, the team’s crest had returned to its traditional colours.

We asked Leonidas Papavasilakis, OFI’s commercial director, why the team’s crest had returned to its traditional colours so fast, and if it was related to the numerous angry reactions and homophobic comments on Facebook. “It was a matter of scheduling. If we were afraid of the reactions, we wouldn’t run the campaign. It was scheduled to last for two days. We’ve been planning it for over a year as a part of the social actions that OFI does every season,” said Papavasilakis.

In their response to Reporters United, Asteras Tripolis FC mentioned “the club’s social profile” and its participation in “European campaigns, such as the #Morethanfootball campaign which is supported by European Football for Development Network (EFDN)”. However, there was no clear answer about the issue, as the reply avoided mentioning the word “homophobia”.

Superleague stated that it shows “zero tolerance for discrimination, racism and violence and through actions tries to inform and raise awareness, promote messages of tolerance, and respect diversity”. They also added that “the matchday 18 of the Superleague was dedicated to the campaign against racism, the promotion of positive messages for humanity, solidarity, respect, tolerance, diversity and equality, with the participation of all teams”. Again, no mention of homophobia. Not even as a term.

PAOK’s reply mentioned that “homophobia is, unfortunately, a social phenomenon that exists in sports and must be tackled in every way. It is a social phenomenon and problem that PAOK Action (PAOK FC’s programme of social activities) considers including in its action plans for the future. However, in previous years there were no actions about the issue”. They also added that PAOK “will examine the issue for the 2021/22 season, which starts in July”.

Lastly, AEL stated that it “is difficult under the current circumstances” to create a campaign against homophobia.

It is striking that although the question we posed was specifically about homophobia in football, none of the replies received – apart from those PAOK and OFI – contain the word “homophobia”. Instead, the replies are around racism and the actions taken to tackle it.

“They don’t want to touch fans’ interests; fans are their customers”, says Daloukas. “At this stage, the Superleague, as the organising authority, could do something more easily than a club. It is much more difficult for a club. Major clubs have made significant improvements in racism but not in homophobia. No one has touched homophobia.”

Ten years of waiting

The first symbolic move against homophobia in Greek football took place in February 2014, with a friendly match between an amateur team, Liberta, and a team consisting of referees of the EPS (Association of Football Clubs) of Thessaly, with the blessings of Football v Homophobia, an international initiative to combat identity discrimination and the expression of sexual orientation at all levels of football.

The organiser of the friendly was the anti-racist organisation foul, which Antonis Daloukas founded. According to the journalist Thanos Sarris in his article in VICE, Mr Daloukas tried to organise a friendly match with the participation of big teams of the country and the blessings of the organising authority, Superleague. But all doors were shut.

According to the Superleague, the reason was that “every year there is a schedule, which includes all the actions of FARE. Because the dates are set in advance, it is difficult to plan anything extra in the middle of the season. This must be done from the beginning of the year.”

In addition, the Superleague stated that “because the teams participate in the social responsibility actions, we cannot add an extra task at the last minute.” They were “confident” that there would be a campaign in the next season’s schedule.

Seven years later, the situation remains the same. The Superleague states that it includes homophobia in the general actions against racism, without mentioning the term “homophobia”, not only in its actions against racism but also in the reply email sent to Reporters United.

“No campaign has been run on the issue, neither by the Superleague, the Greek FA Federation, nor the clubs”, Daloukas says. “Nothing has been done. In a series of recently announced actions, again, there is nothing. Any improvement I see is in society, not football. We know that football is more difficult than other sports in terms of receptivity because most people believe football is associated with manhood and masculinity.”

The “customers” and the environment

The environment is the most crucial element that a gay footballer considers when he wants to come out. The football pitch is a challenging environment where homophobic slurs are constantly used in chants. Even if these slurs do not target a gay person, they are used as an insult.

Although homophobia in football is not a phenomenon that only affects Greece, an effort is being made to combat the phenomenon in other countries. In Britain, almost all clubs have fan clubs made up exclusively of members of the LGBTQ+ community, such as Arsenal’s Gay Gooners, Chelsea’s Chelsea Pride, Liverpool’s KOP Outs and more. The clubs themselves campaign against homophobia while supporting actions such as Pride.

Often, while the environment can be more supportive within a football club – where players will support and embrace a gay footballer – there is an omerta outside the changing rooms. A footballer can talk about his sexual identity to a teammate, but he can not do so in public due to toxic masculinity and sexism among the fans of the teams.

“Homophobia is so intertwined with football culture that it is certain that if a player comes out, he will be a constant victim of homophobic insults”, explains Daniel Khan, member of Football v Homophobia.“In addition, agents advise footballers not to come out, as this will affect the player’s monetary value as teams are afraid to invest in a gay footballer. Changes need to come from above – for example, from clubs and domestic football associations – to influence fans as well to ensure a safe environment for members of the LGBTQ+ community, whether we are talking about footballers or fans”, Khan adds.

In August 2020, the owner of AEL, Alexis Kougias, in an official club statement against the former owner of Xanthi, Christos Panopoulos, used homophobic slurs, while adding for good measure that “in my way of life and my social environment, men do not like men.”

Neither the Superleague, nor the Greek FA, nor any sports judge called on Alexis Kougias to apologise for this statement. They remained silent.

In 2017, Vassilis Tsiartas, a former player of AEK FC and the Greek national team, wrote a post on social media opposing the gender reassignment bill which was going through Parliament. Tsiartas’s Facebook post stated that “a couple only consists of a man and a woman” and that he “will not accept anything different.” Tsiartas went to urge the Greek political parties to legalise paedophilia, in an attempt to equate homosexuality with paedophilia. Neither AEK, the National Team, nor the EPO took a stand on Vassilis Tsiartas’ posts. Again, silence.

The first (and last) survey on homophobia in Greek football

Fourteen years ago, Antonis Daloukas – through the foul organisation – conducted a survey on homophobia in Greek football. Daloukas decided to carry out this study when, as an observer of racism in UEFA matches, he saw that in other countries, members of the LGBTQ+ community could watch a football match without fear. The proposal for this research was made to the EGLSF (European Gay & Lesbian Sport Federation), whose members were surprised that someone from Greece wanted to investigate the issue, according to Daloukas.

The survey, entitled “Offside”, lasted three months, and 1,000 people participated in it. The participants were team fans, parents, referees, coaches, amateur and professional athletes. The results were presented by Daloukas in Antwerp, but were ignored by the Greek clubs, the Greek organising authorities and the Greek FA. It is indicative that the research – although it is the only survey to have been carried out on the subject in Greece – disappeared from the internet when the website of the foul organisation ceased to exist. It’s as if almost no one wanted to continue to have this research on the internet available to everyone.

The research, which Reporters United presents here exclusively, shows that:

• 55% of the participants would not have a problem if one of the team’s football players they support comes out

• 43% would have no problem if one of their teammates were gay

• 46% would not have a problem with a gay coach coaching children

• 44% have seen homophobic attacks in Greek football

• 81% of the participants think it is extremely difficult for a gay footballer to come out in Greek football.

“The results of the study were expected. Of course, there are gay footballers, but it is hard for them to come out. They will probably never come out. I find it very difficult to have a fan club in Greece consisting exclusively of members of the LGBTQ+ community, as it happens abroad. However, it disappoints me that after so many years, we have not seen any sign of improvement on the issue in Greek football,” says Antonis Daloukas, 13 years after this research was carried out.

The “blind spot” of the Greek FA Code of Discipline

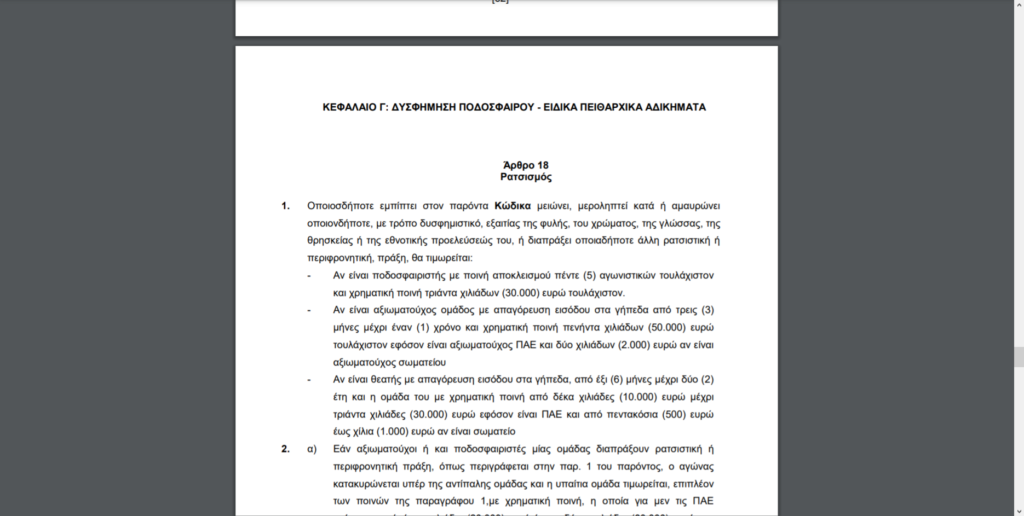

In Chapter C of the Greek FA Code of Discipline for 2020, Article 18 on Racism, states that “anyone who discriminates against or tarnishes anyone, in a defamatory manner, because of race, colour, language, religion or ethnic origin, or commits any other racist or derogatory act, shall be punished”.

Even though the Code lists other types of defamation, discrimination against sexual identity or preference is absent. At the same time, anyone who wants to make a homophobic statement (football player or official) will most probably not be punished.

“UEFA has decided that the money raised from the fines paid by each country for cases of racism or homophobia will be invested in researching these issues, but also in promoting messages,” said Antonis Daloukas. The question, however, remains how Greece can participate in a program which invests money from fines in anti-homophobia surveys, when the entire domestic football community pointedly ignores the existence of the issue even on a social level.

“Football still has a traditional element in its nature, that it is a sport only for boys. So even if people want to make campaigns, there are still traditions and stereotypes”, says Beatrice Thirkettle of Football v Homophobia. “I think it will be positive if we see clubs starting to support campaigns like Pride”, she adds. “It will be useful for them to find ways to highlight the problem and have a long-term effect”.

What’s to be done

A solid first step would be to include the term homophobia in the forms of racism prohibited by the Superleague and the Greek FA. The issue cannot be addressed without recognising it. Positive campaigns can also help, and there are successful models for this. At Champions League matches, there is an obligation to play a 30-second video on racism. Airing time has been secured to show these videos featuring famous footballers such as Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo.

“I strongly believe in the power of football stars. It is crucial to the fans. It would be very different if a top player of Olympiacos, PAOK, or Panathinaikos came out to support Pride. Or a leading club in Greece“, Daloukas says. In the UK, football players such as Arsenal’s Hector Bellerin and Chelsea’s Olivier Giroud have openly sided with the LGBTQ+ community, with the blessings of their clubs and the English Football Association.

However, the question remains, which famous Greek footballer would be the first to talk about the issue publicly, stand by those subjected to homophobic attacks, and participate in campaigns against homophobia.

It is a long road until the day a gay football player will step on the pitch without the fear of homophobic attacks and outcry. A receptive football environment is essential not only for the LGBTQ+ community but also for football itself.