Editing and data analysis: Georgia Nakou

Aegean Airlines has been Greece’s de facto flag carrier since the dismantling of Olympic, with the prestige and privileged treatment that goes with that title, despite being privately owned. This was the logic adopted by the Greek government when it announced a special pandemic rescue package for the airline in November 2020, describing the bailout as a “national duty”.

Since launching in 1999, Aegean has not only become Greece’s dominant passenger airline, but has been voted “Best Regional Airline in Europe” in the Skytrax World Airline Awards for nine years running, and topped Fortune magazine’s list of “Most Admired Companies in Greece 2019”. If industry plaudits are anything to go by, the airline is not only popular to travel with, but also to work for. Aegean was named “top employer to work for in Greece” in a 2020 Employer Brand Survey by HR consultancy Randstad.

Those who have been on the inside, however, tell a different story. Reporters United spoke to current and former employees of the company over the course of several months, and their accounts paint a picture starkly at odds with the company’s public image. The company is a member of the elite Star Alliance network, but our investigation shows that in some respects its employees have fewer rights than their colleagues in the low-cost airline sector.

Our conversations took place during the pandemic, when crews were largely grounded, and the airline was kept afloat by a state rescue package estimated to total over 340 million euros. We interviewed nine current and former Aegean employees, including cabin crew and administrative staff, whose accounts span fourteen years of the company’s operation from 2008 to the present, relating to practices at the company both before and during the pandemic.

Temporary contracts for permanent needs

According to employee accounts, many among the airline’s cabin crew are not permanent employees of Aegean, but are employed on “intermittent” fixed-term contracts. This means working for three consecutive short-term contracts, or a total of 18 months, and then ending their employment relations with Aegean for 45 days, before being re-engaged on another fixed-term contract. The merry-go-round of fixed-term contracts and 45-day intervals has been known to go on, with the employees’ consent, for as long as nine years, according to our sources’ accounts. This was the experience of all the current and former Aegean cabin crew we spoke to.

Reporters United asked Aegean what its policy is towards female employees who get pregnant. The company did not respond to the question.

Many of the crew say they took odd jobs, went travelling, or claimed unemployment support during those intervals, while never knowing for sure whether they would be rehired.

Why 45 days? According to Greek employment law, fixed-term contracts which exceed 18 months’ duration or three consecutive renewals must be converted into permanent positions. The 45-day interval protects the employer from this obligation, which would confer full employment rights on the worker.

This intermittent arrangement absolves the employer of the obligation to pay compensation for dismissals, which in the case of a permanent employee of nine years would total five monthly salaries. Fani*, one of our sources for this story, who was not rehired after working a total nine years on fixed-term contracts, was entitled to nothing.

“To survive, you had to be very thin”

Tina, 36, worked at Aegean for almost eight years.

Sick leave and maternity leave are also drastically curtailed, and there are no automatic salary increases, which in the case of permanent staff add up to 10% for every three years of service.

Reporters United asked Aegean what its policy is towards female employees who get pregnant. The company did not respond to the question.

Reporters United also asked Aegean to explain its use of fixed-term contracts. Its response stated the following:

“In recent years, prior to the outbreak of the [pandemic] crisis, out of approximately 3,000-3,100 staff employed over the summer season, roughly 2,400-2,600 have also been employed in the winter, despite the fact that our winter flight activity is just 40% of the summer. It is clear that seasonal contracts are necessary due to the large variation in activity levels”.

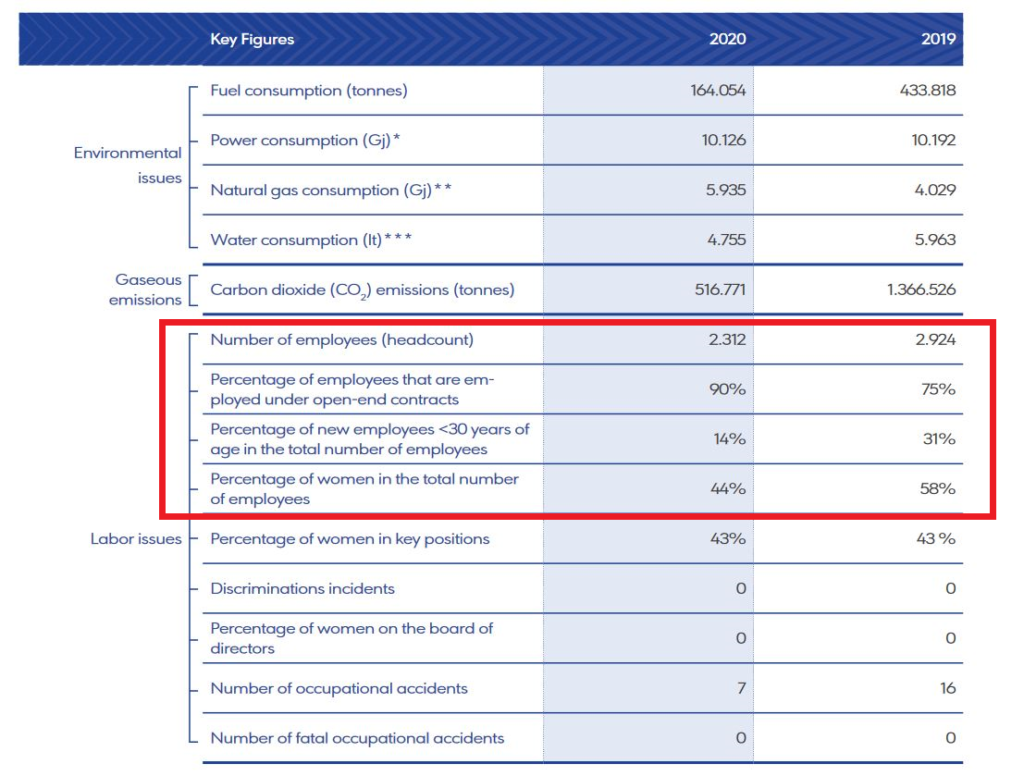

Figures published in Aegean’s 2020 annual report offer some further insights into the prevalence of the practice. It states that in 2019, 75% of staff were on permanent contracts, rising to 90% in 2020. From this we can conclude that 25% of employees were on fixed-term contracts in 2019, and 10% in 2020.

The “beauty list”

In addition to regular employee appraisal records relating to flight hours and performance, some of the former employees we spoke to told us that the company maintains what is referred to internally as “the beauty list”.

Three former cabin staff told Reporters United that the “beauty list” scored cabin crew on appearance. “To survive, you had to be very thin”, says Tina, 36, who worked at Aegean for almost eight years.

Anna described an incident where her superior, the female head of the air cabin crew called in a colleague, “so that I would be weighed in front of an audience, which was soul-destroying”.

Every October, at the start of the winter season, the company would carry out a so-called “clearout”. Cabin crew went through interviews, during which they were also weighed. Those found to be carrying an extra 2-3 kilos would be reprimanded and would have to lose it. According to Tina, weight gain was frequently used as a pretext to refuse contract renewals.

Anna, 31, currently unemployed, worked for the company for six years. She claims that she had been on the receiving end of comments about her size. She wore dress size 40, “but they wanted the girls to wear size extra small, even extra extra small”, she says.

Anna described an incident where her superior, the female head of the air cabin crew called in a colleague, “so that I would be weighed in front of an audience, which was soul-destroying”.

Anna was never offered a permanent contract. The main justification she was given was that the Aegean uniform was too short on her, and because her performance was low compared to that of one of her colleagues. “They told me they knew my weight was fine, but the dress was too short on me”, she tells us. “My uniform was always clean and pressed. I put on body mass, it is not fat. After those nine months, I was filled with doubts. I had come to realise they only wanted me for skivvy work”.

“After the age of 30, you realise that your days with the company are numbered”, Tina adds. Maria, 38, who worked as cabin crew for almost nine years, adds: “The timetables and flight hours are the same for all cabin crew, regardless of age, in contrast to airlines abroad which relax their scheduling for older workers, to give them more flexibility”.

Since 2011, there has been no union representation in one of Greece’s largest employers.

Gender-biased workplace harassment, including humiliating practices such as weight checks and forced retirements at a young age, is widespread in the airline sector.

We asked the airline to comment on these claims. Aegean did not respond to our question about whether there was direct or indirect harassment of female cabin crew in relation to their weight or appearance, and whether weight could be a reason for non-renewal of contracts.

Union busting

Workers at most airlines, and particularly the big flag carriers, are represented by unions, and in some countries have workers’ representatives on the board, arrangements which make it harder for the airline to dictate employment terms unilaterally.

Aegean employees were only allowed union representation for a brief period. Christos Karagiannis, president of the Greek Federation of Aviation Personnel (OPAM) told Reporters United that a union was formed in late 2004 and operated until 2011, with a membership which reached 140.

During that period, two collective agreements were signed, one of which with the mediation of the Greek Organisation for Mediation and Arbitration (OMED). “From its side, the company tried to weaken the union in every possible way”, Karagiannis told us.

When Aegean outsourced its ground activities to Goldair, the union lost most of its members as it was heavily tilted towards ground crew. Other members were gradually transferred to other posts within and outside the company, and the union eventually became obsolete.

In the decade since, there has been no union representation in one of Greece’s largest employers.

Which club does Aegean belong to?

Reporters United approached Lufthansa, posing similar questions to those we asked Aegean. (Lufthansa is a member of the Star Alliance club along with Aegean and a number of other national carriers, including Air Canada, TAP Portugal and Singapore Airlines.)

Lufthansa’s response detailed its policies on employee appraisal in relation to weight. The airline told us that it carries out annual checks on its cabin crew to determine their fitness to fly, in which weight is only one factor in assessing their general health. Lufthansa’s claim was corroborated to R•U by German union Unabhängige Flugbegleiter Organisation (UFO) which represents, among others, the cabin crew of Lufthansa and Ryanair.

The contrasts do not end there. Lufthansa stopped imposing fixed-term contracts on its workers in 2014 after pressure from unions, and now only hires staff on permanent contracts.

A major survey of the aviation industry produced on behalf of the European Commission in 2019 found that up to 20% of cabin crew in Europe work under what are termed “atypical” employment arrangements, including through temporary work agencies or on zero hours contracts in a shadow “GIG economy”. The vast majority of instances (up to 97%) relate to budget airlines.

AEGEAN made the least possible contract terminations, which did not exceed around 5% of staff (obviously in total accordance with employment law), a much lower percentage than state and private airlines in Europe.

Aegean Airlines, response to Reporters United

Atypical arrangements include what one aircrew union called “permanent seasonal” arrangements based on rolling fixed-term contracts, which mirror those described by the Aegean employees (but for the fact that the work is contracted through an intermediary). The authors of the report considered this arrangement abusive because the company’s resource to “temporary” work is in fact permanent.

In Aegean’s case, despite being a member of Star Alliance, an elite club of national carriers, the airline appears to have adopted an approach to worker’s rights which puts it more in line with worst practice in the budget airline industry.

In some respects, it has been allowed to go further. Unlike Aegean, even Ryanair was forced to recognise unions in some European countries in 2018.

Rescue for the company but not the workers

During the pandemic, the airline received a rescue package from the Greek government, consisting of a cash injection of 120 million euros, plus state-guaranteed loans totalling 150 million, and other economic support measures estimated to bring the total to over 340 million euros.

Reporters United asked Aegean to detail the total value of the rescue package but did not receive an answer.

In comparison to other rescue deals struck during the pandemic which are detailed in a 2021 OECD report, the financial support given to Aegean was small compared to the multi-billion euro packages received by other European airlines. However, it came with very few strings attached. The deal required existing shareholders to put an additional 60 million euros in the company and gave the state an option on shares, but Aegean’s peers had to comply with much more onerous terms, ranging from part-nationalisation to mandatory emissions targets. In many cases they had to agree to limits on layoffs or other employment protection measures.

In its response to Reporters United, Aegean argued that the internal recapitalisation was “a condition that was implemented for the first time in Greece”, adding that “compared to countries with a comparable GDP and population, such as Portugal, but also Germany, France, etc., the degree of support is far smaller, always in relation to the size of the enterprise”.

Discussing a potential rescue package in 2020, Aegean’s Chairman Eftichios Vassilakis told an industry panel that he hoped the state would intervene “to help us while we are struggling to keep on as many people as we can, or offer them a bit more than we can afford to”.

The airline, however, proceeded to make numerous layoffs during the pandemic. Christos, a former employee in the company’s offices, recalls “tens of layoffs taking place at the end of each month”, when he would find “colleagues crying the hallways having just been dismissed”.

In its 2020 annual report Aegean states that it employed 2,926 staff in 2019, while the number was cut to 2,312 in 2020 — a net headcount reduction of 612, or 21%.

Unlike the majority of European airlines Aegean did not publicly disclose its layoff plans. Reporters United asked the company how many employees it let go during the pandemic.

The company did not provide figures but responded only to say that “contract terminations did not exceed 5% of staff (obviously in full accordance with employment law)”, describing the percentage as “much lower than state and private airlines in Europe”.

The figures in the company’s annual report tell a slightly different story. Aegean states that it employed 2,926 staff in 2019, while the number was cut to 2,312 in 2020. This equates to a net headcount reduction of 612, or 21%.

What accounts for the difference? We calculate based on their figures that out of the 612 jobs lost, 500 relate to fixed term-contracts while 112 were permanent positions.

Based on our calculations, this means that Aegean’s figure of 5% accurately describes cuts to permanent jobs.

However, the company achieved the lion’s share of its headcount reduction by not renewing fixed-term contracts. For every permanent job terminated, the company cut four fixed-term positions.

The reliance on fixed-term contracts, therefore, allowed Aegean to cut jobs without being burdened with compensation costs, while apparently respecting its legal obligations to permanent staff.

There have also been allegations that the company forced furloughed workers to work remotely for extended hours. The claims, made by PAME, a trade union confederation affiliated to the Greek Communist Party, were corroborated by one of our sources. Christos told us that those who kept their jobs were made to work extra hours under stressful conditions, even while they were on suspended contracts or working part-time under pandemic employment protection measures.

Aegean’s pandemic jobs cull disproportionately affected younger workers, who fell from 31% to 14% as a proportion of the total headcount (a reduction by two thirds in absolute terms), and women, whose representation fell from 58% to 44%.

Friends in high places

When presenting the airline’s rescue package to Parliament in late 2020, Infrastructure and Transport Minister Kostas Karamanlis argued that the measures were a necessity because “Aegean has all the features of a national airline, and the support is necessary for the survival of our tourist industry”, adding, “The government has decided to support it for reasons of national interest”. In effect, he was arguing that in the context of the Greek economy Aegean is too big to fail.

Some of the company’s support may spring from more personal connections. Aegean is 100% privately owned, and controlled by some of Greece’s most prominent business families. The majority shareholder is Efthichios Vassilakis, who inherited a 36.64% stake from his father Theodoros, while the Laskaridis brothers (with significant business interests in shipping, fishing, tourism, and casinos) own 9.48% each through the companies Alnesco and Siana, and Achilleas Konstantakopoulos, whose family controls the Costamare shipping business and the Costa Navarino resort, owns 6.39%.

Both Vassilakis and the Laskaridis brothers have personal links to the family of Greece’s current Prime Minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis. In 2009, Vassilakis’s business rival, the late Andreas Vgenopoulos, then owner of Olympic Airways, accused Mitsotakis’s sister, the then Foreign Minister Dora Bakogianni of siding with the Aegean in the fierce competition for licenses between the two airlines, to the detriment of the public interest.

The Laskaridis brothers have been linked in the press to an offshore company which helped fund Mitostakis’s wife Mareva Grabowski-Mitsotakis’ foray into the fashion business with the Zeus+Dione label (the claim was put to the Laskaridis brothers as part of another Reporters United investigation).

All current and former employees of Aegean spoke to Reporters United on condition of anonymity. The names used in the story are not their real ones. Their identities are known to Reporters United.

Great reporting! It would be great to offer a substack subscription option for us that want to support your effort

I understand how airlines have had to let go of staff during the pandemic and I also understand they have to keep their image, hence no overweight cabin crew (keeps down fuel costs) but it’s despicabke to not pay a liveable wage and to make staff sign renewable contracts. Aegean has no class!