This is a collaboration between Solomon, Investigate Europe and Reporters United. So far the story has also been published by Open Democracy (UK), Vice (Germany), Klassekampen (Norway) and WP Magazyn (Poland).

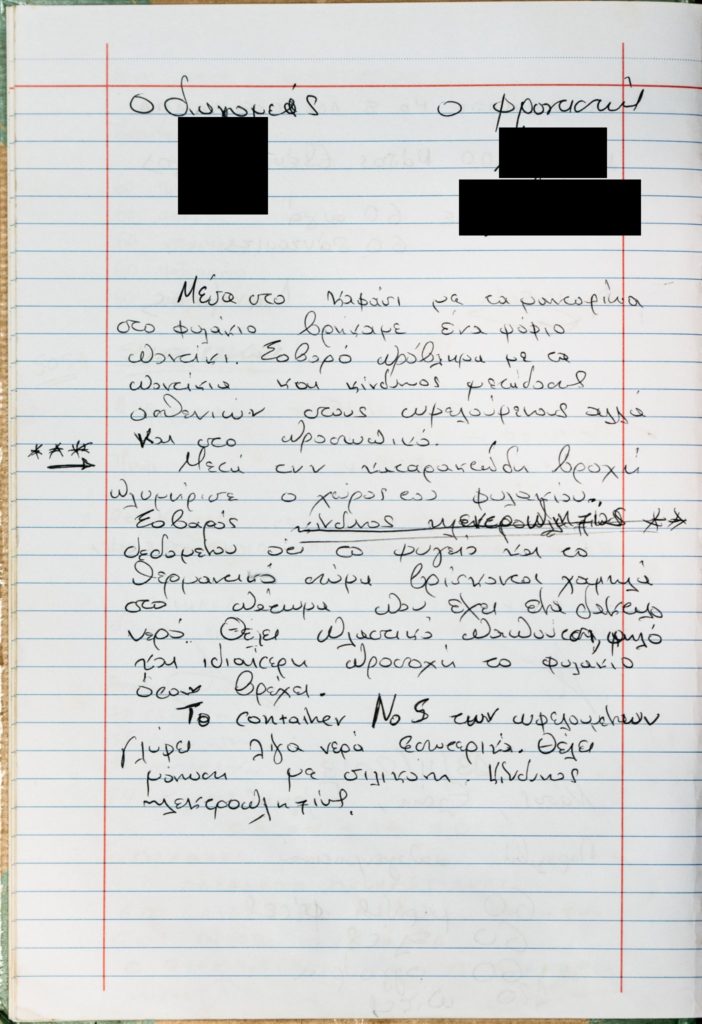

It’s a cold morning in November 2018, when a care worker in Moria’s “safe zone” makes a revolting discovery. Fanis* walks into the guardroom to pick up a box of mandarin oranges for the children. Inside the box, among the fruit, he finds a dead rat.

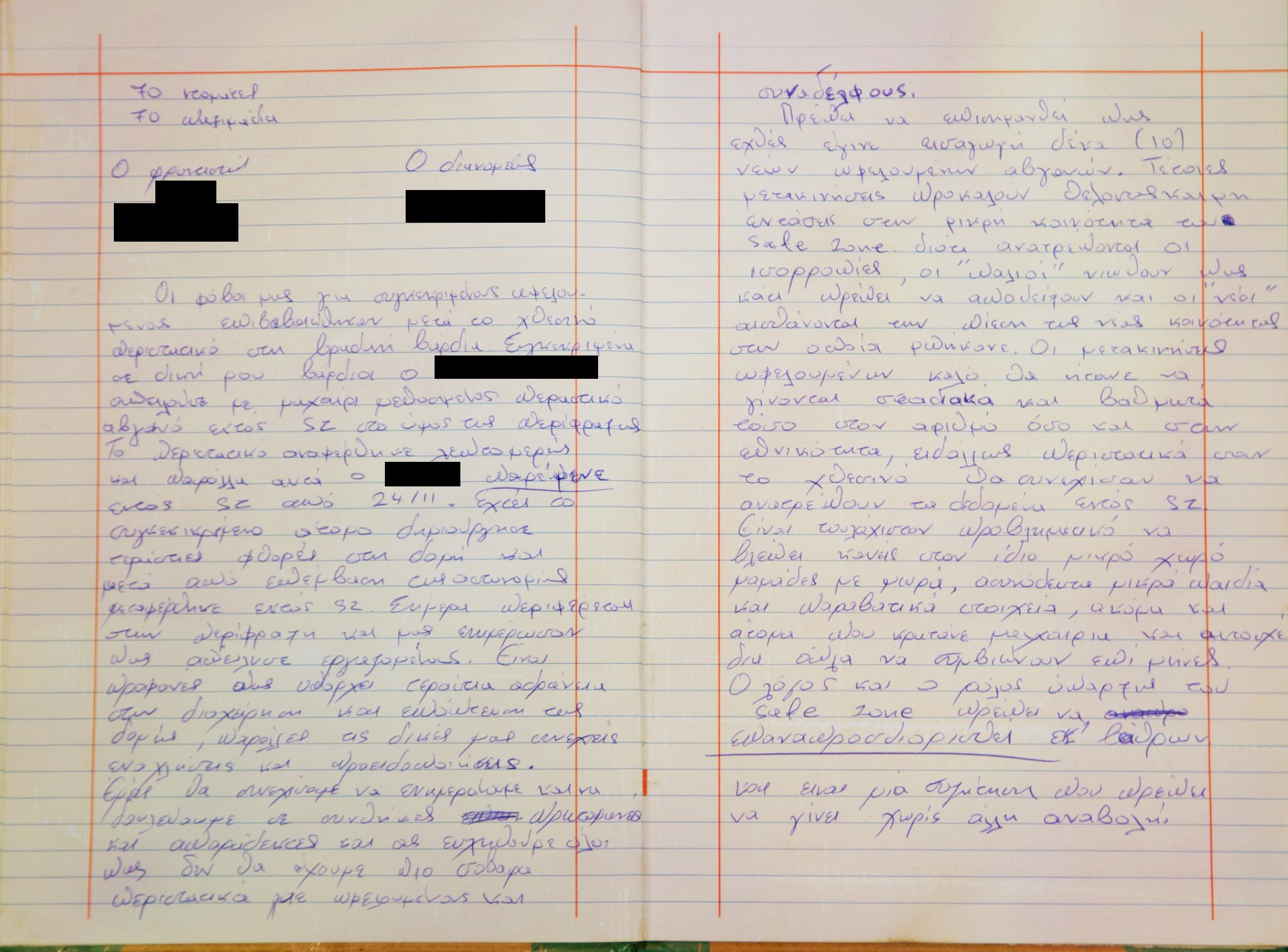

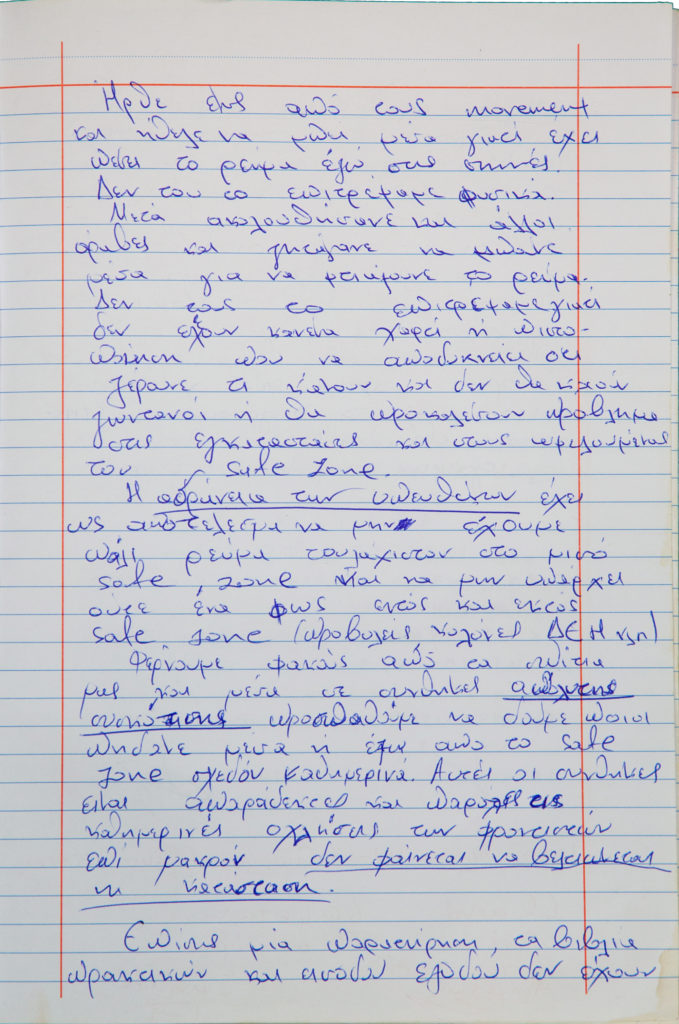

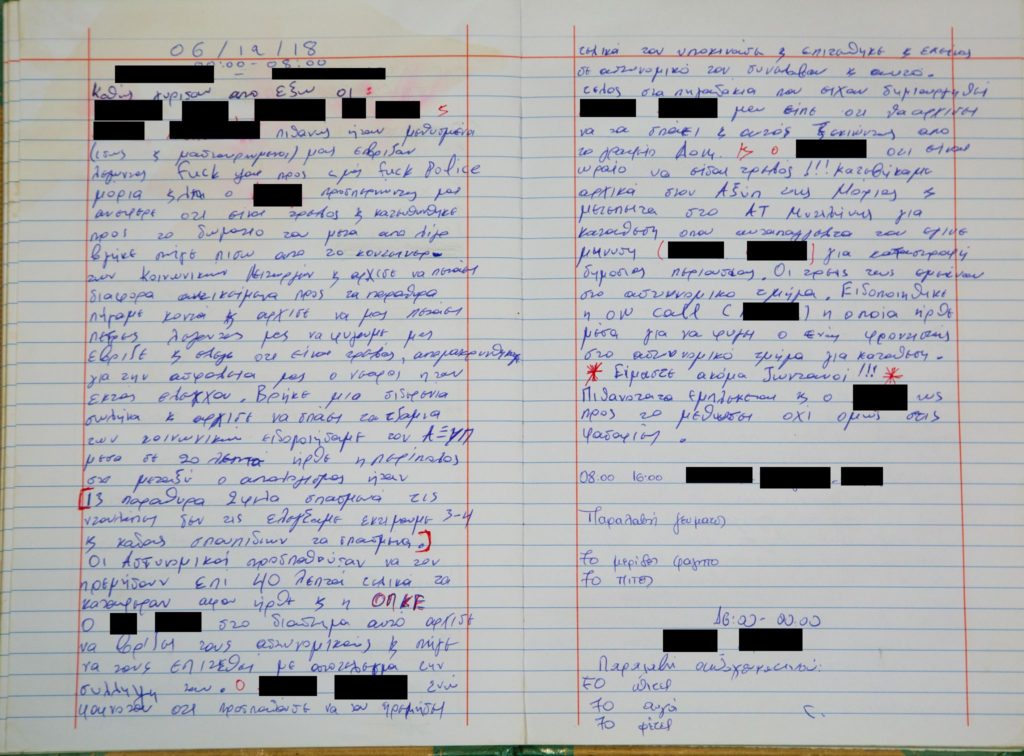

It’s not the first time this has happened. “Serious problem with the rats, and danger of infusion of diseases to the beneficiaries and the personnel,” the care worker notes down in a hardcover logbook at the end of his shift.

This was not his only concern that morning.

The massive rainfall of the night before has flooded the guardroom, Fanis goes on to write; it is the room where the fridge and the heating unit are located. The rain has also seeped into ‘Container No 5’, which houses some of the unaccompanied minors in the camp.

Without silicone insulation and protection, he warns, the situation remains unsafe and puts lives in danger. “Major danger of electrocution,” the social worker writes, before he puts his pen away and shuts the notebook.

A notebook that documents Moria’s horrifying story

Till the evening of September 8, 2020, when multiple fires razed it to the ground, Moria had been Europe’s most notorious refugee facility, synonymous for years with dehumanising and dangerous conditions for its thousands of residents.

Walking around the burnt periphery of the camp — which is located on the Greek island of Lesvos — in the aftermath of the fire, in what used to be the so-called “jungle” (a former olive grove surrounding the initial structure on which hundreds of makeshift tents were set up), one of the two authors of this article, reporter Stavros Malichudis, found a notebook. It was nestled in the ground, amid destroyed tents, burnt possessions, and soot that painted the area black. The hardcover exterior of the book possibly helped it survive the fire. Its contents cover a time span of roughly six months, from November 3, 2018 to May 7, 2019.

It appears to be the day-to-day diary that was maintained by at least eleven employees of the “International Organization for Migration”, an intergovernmental organisation that is affiliated with the United Nations and was responsible for the so called “safe zone” in Moria. According to IOM, its team at the safe zone consisted of “child protection workers, psychologists, lawyers, care workers, nurses [and] interpreters to assist children and cover all of their needs.”

The safe zone was where the unaccompanied minors in the camp lived under supervision, often for months, while they waited to be transferred to the Greek mainland or to other European countries. The fenced area was set up to provide these minors with better protection than was available in the rest of the camp. They were allowed to leave during the days, but should stay inside at night.

Moria’s unsafe living conditions have been reported extensively. At the beginning of 2020, Reporters United and Investigate Europe published an investigation about the jailing of minor migrants who were made to live across European countries. As part of this investigation, IE also reported about the unsafe conditions in Moria.

The entries of the notebook, discovered in the ashes of Moria, confirm the shocking reality that Europe’s most vulnerable asylum seekers were left to endure. Written from the perspective of the people who were there to protect the unaccompanied minors, it reveals their helplessness and inability to do so. Care workers, like Fanis, also used the book to raise an alarm and complain about the inaction of the authorities.

The logbook reveals the constant, never-ending technical insufficiencies, the deep psychological struggles that the minors experienced because of their confinement in Moria, and the dangers awaiting them in every corner — not just outside the safe zone, but inside it as well. It depicts a reality in which the danger of electrocution seemed not only to be embedded in everyday life, but was far from being the sole concern.

All quotes are attributed exactly as they were written by the social workers (translated from Greek), and all underlined words and punctuation follows the original text by the care workers in the logbook.

Constant darkness over the safe zone

Lack of electricity — caused by heavy rainfalls or other incidents — is an issue that often appears in the 190 pages of the logbook. Sometimes, the problem was not fixed for days. Checking who attempts to enter or exit the safe zone becomes then a challenging task. After all, it is the care workers’ task to make sure the minors are safe while they are in the safe zone.

An absence of electricity at night means that the staff are unable to supervise the two sides of the barbed wire, which is what separates the safe zone from the rest of the facility. So, on November 24, 2018, with a power shortage that had already lasted several days, one of the care workers on shift opens the notebook. It is the shift of Fanis, Maria and Giannis. Their tone sounds desperate.

“The inaction of the people in charge is resulting again in us not having electricity, and not having even one light inside and outside of the safe zone. Almost daily, we bring torches from our houses, and in conditions of full darkness, we try to see who jumps inside and who jumps outside of the safe zone. These conditions are unacceptable, and no matter the daily complaints of the care workers for long, the situation does not seem to be improving.”

The personnel’s worry seemed well-warranted. When the minors were outside of the protected area, almost anything could happen to them.

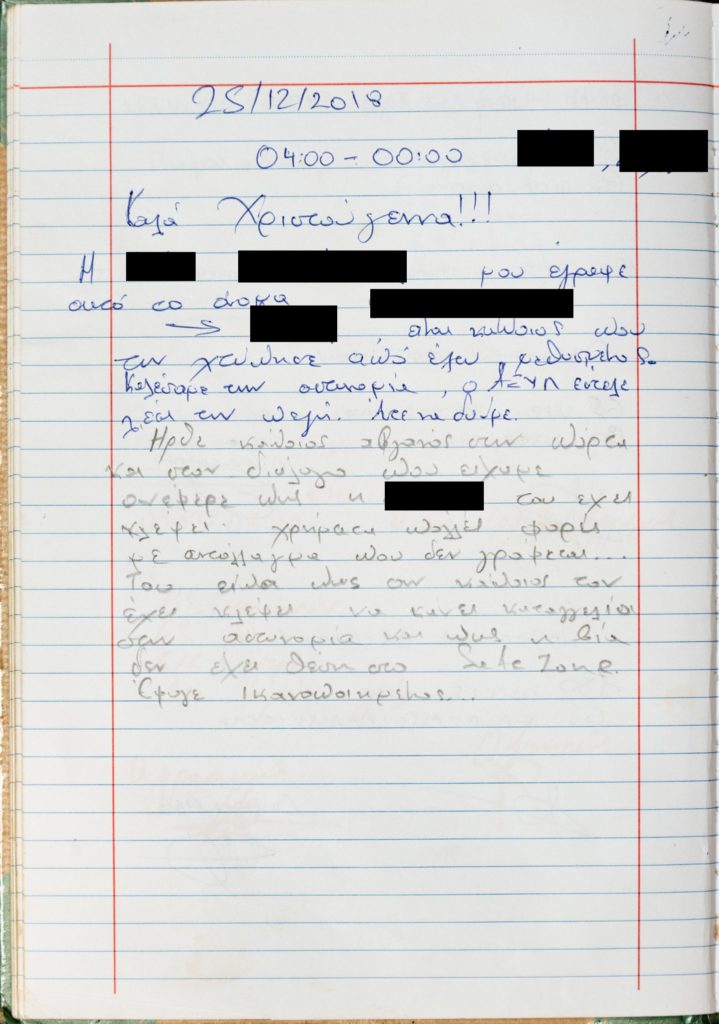

A Christmas note…

On the top of the page, a “Merry Christmas!!!” in big, clear letters stands out among other notes that appear to be hastily written. It is 25 December 2018 and S., a female minor who resides in the safe zone, has just passed a piece of paper with a name on it to the social workers.

It is the name of her abuser. The care workers jot the name down on the book with a pencil, among other notes made with a blue pen.

“It’s someone who beat her outside of the safe zone while he was drunk,” they add. “We called the police, the officer sent the patrol officers. Let’s see what will happen.” The entry is signed by Fanis and Dimitris — their resigned tone indicating that they don’t actually expect much action to be taken.

Earlier that day, a man had approached the entrance of the safe zone (it’s not clear from the log whether it’s the same man). While talking with the care worker, he accused the minor girl, S., of stealing money from him. The man had given her money on many instances, he claimed, “in exchange for things that can’t be described…”.

The social workers had sent him away, telling him that if someone had stolen money from him, he should go to the police, and that violence has no place in the safe zone. “He left satisfied…,” the notes say, leaving it unclear whether there were consequences for the man or whether the abused girl received the necessary help.

In related questions addressed to IOM from Solomon, Investigate Europe and Reporters United, IOM answered that “psychological support to children to prevent or address any arising conflicts” was granted under its supervision.

…and minors’ encounter with Moria’s reality

Sexual exploitation, as implied in the above incident, is one of the dozens of dangers that minors face from the moment they cross the fence to enter the safe zone. Other major problems include alcohol or drug abuse or getting involved in serious fights.

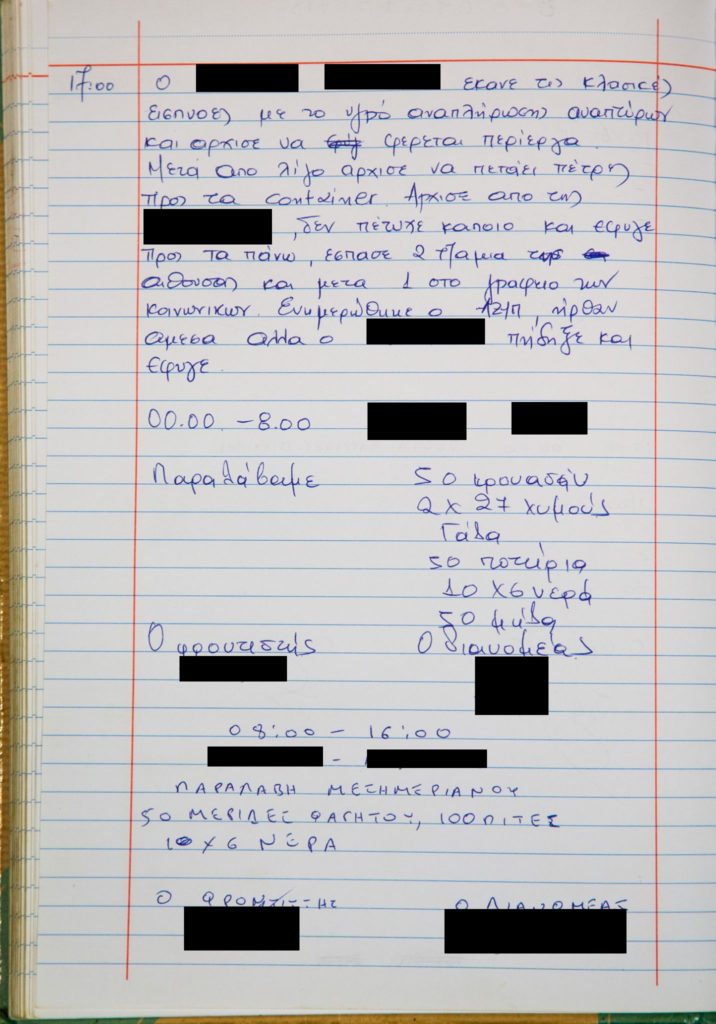

On the evening of April 6, 2019, male minor N. is reported to “have made inhalations of the liquid used to refill lighters, as usual, and started to act in a weird way”. After some time, he starts pelting stones at the containers, smashing windows. “The officer was informed, they came quite quickly, but N. jumped off the fence and left,” states the entry.

There are numerous cases reported in the logbook, sometimes on consecutive days, describing minors who return to the safe zone drunk or stoned. In some cases, they cause disturbances to the other residents or care workers, engaging in altercations.

“Fuck Moria!”

Sometimes, the care workers appear to be unable to handle a situation and need to ask for the intervention of the police present in the camp to calm things down.

“We are still alive!!!” a note signed by the care workers Dimitris and Iosif concludes on the night of December 6, 2018. “As Q., H. and A. came back from outside, they were probably drunk (maybe even high) and insulted us by saying ‘fuck you, fuck police, Moria’ etc.”

Verbal insults are not the only thing that take place that night. The logbook provides a detailed description of the events that happened before the police — after trying for 40 minutes — finally managed to calm down the minors, eventually taking the three boys to the police station.

“It’s nice to be crazy,” the minor named Q. keeps on shouting to the care workers. His outburst is translated into a number of damages: “There are 13 windows broken, we did not check the closets, but estimate three or four of them too, and rubbish bins are also among the broken items.”

Tensions among the minors

It has been reported before that the overcrowded and dire conditions in the Moria camp fuelled tensions between residents of different ethnic and national groups.

In the winter of 2020, Reporters United and Investigate Europe published findings about the dire conditions endured by minor asylum seekers across the continent, including Moria. “They stand in line. There are queues in front of the toilets. There are queues to shower, often in cold water,”we wrote in our report. Swedish aid worker Patric Mansour, who had worked in Moria since the early launch of the camp, told us that the high levels of stress and frustration were created by an everyday life that was governed by “delays in all areas”.

“All the frustration is placed on the individual, who lives in uncertainty,” he said. “There is violence and crime. People fight for little things because of stress”.

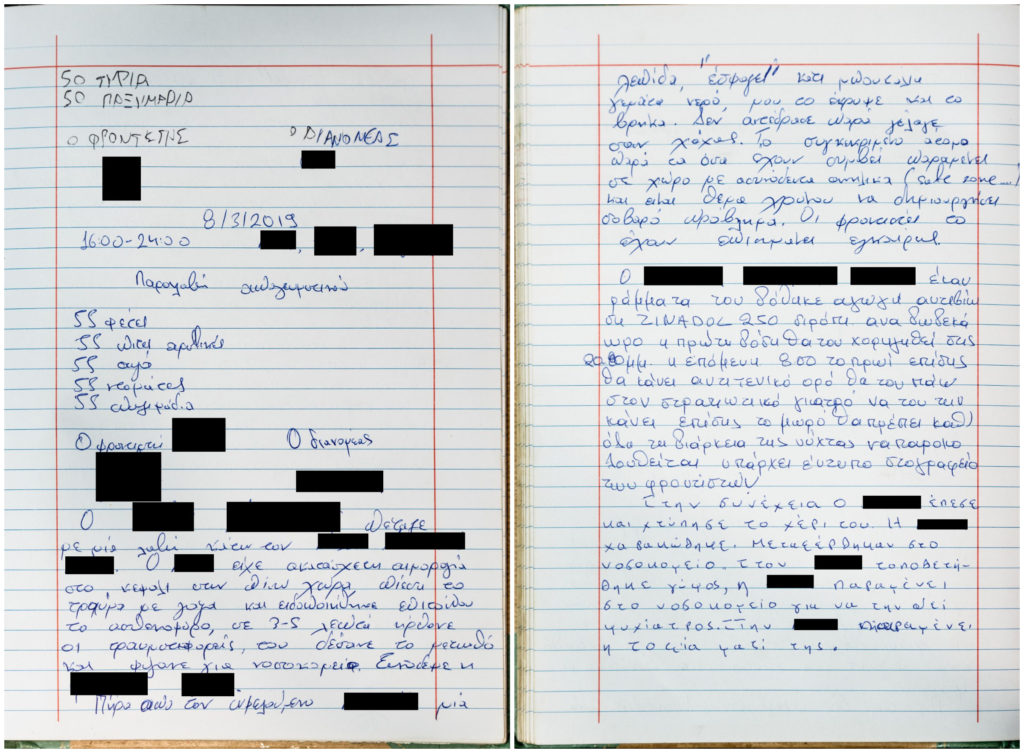

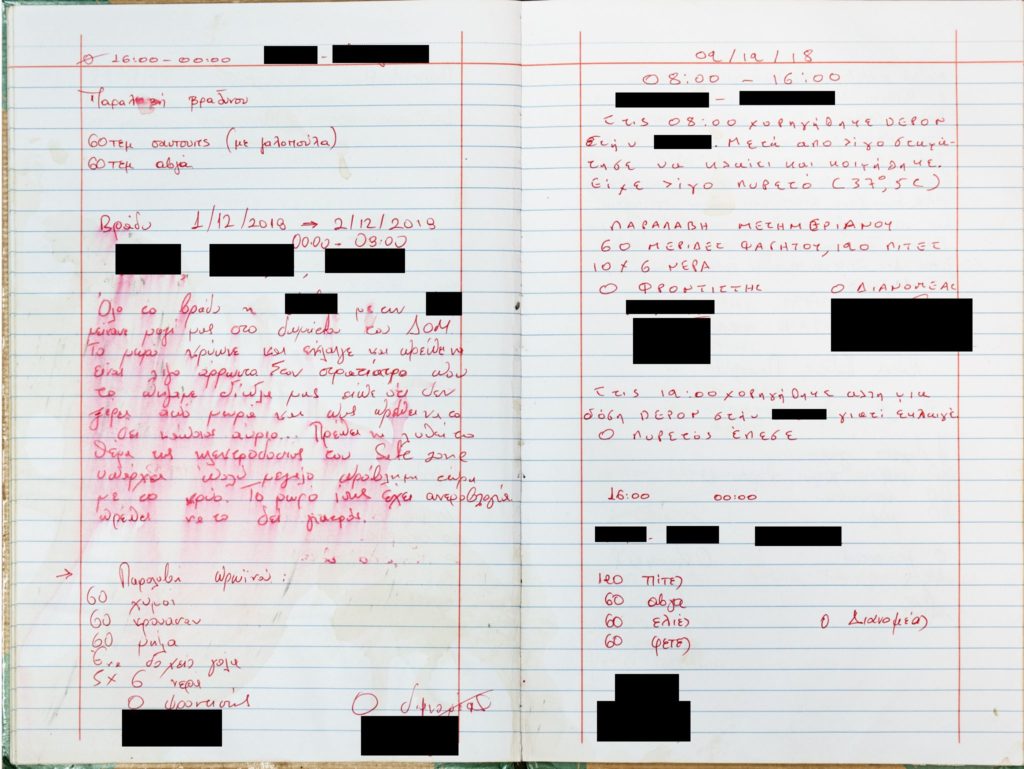

The logbook shows that minors were also affected by the violent conditions in the camp and violence is transcribed as part of everyday life. For example, on November 26, 2018 a fight among two boys leads to one more getting involved, and finally ends with one of them being taken to the doctor.

A week later, on December 2, 2018, two brothers attacked a third boy with an iron and a wooden pole. Incidents like the ones above are often mentioned in the care workers’ entries, with a tone that shows that they are not surprising.

Health issues in the safe zone

Sometimes though, the minors direct the violence towards themselves.

On November 6, 2018, the female minor S. — who would later report about the abuse — harms herself with a razor inside the girls’ showers, and is brought to the doctor. “The wound was deep,” says the entry. On March 8, 2019, another female minor, mentioned as A., also cuts herself and is brought to the local hospital to be seen by a psychiatrist.

Other entries in the notebook similarly highlight the psychological traumas experienced by the children in the camp.

Intervention by the camp’s military doctor is often needed, and in a number of cases, minors have to be escorted to the island’s hospital. Even so, they do not always receive the help they need.

On the night of December 1, 2018, a baby who lives with her teenage mother in the girls’ section does not stop crying. “We took [the baby] to the military doctor of the camp, but he told us that he has no expertise on babies and that someone should see it tomorrow,” the care worker writes, adding that the baby could possibly have chicken pox.

That night, the work in the safe zone is once more affected by the power shortage, making it unable to provide the baby with any heating against the cold December night.

Repeated warnings fall on deaf ears

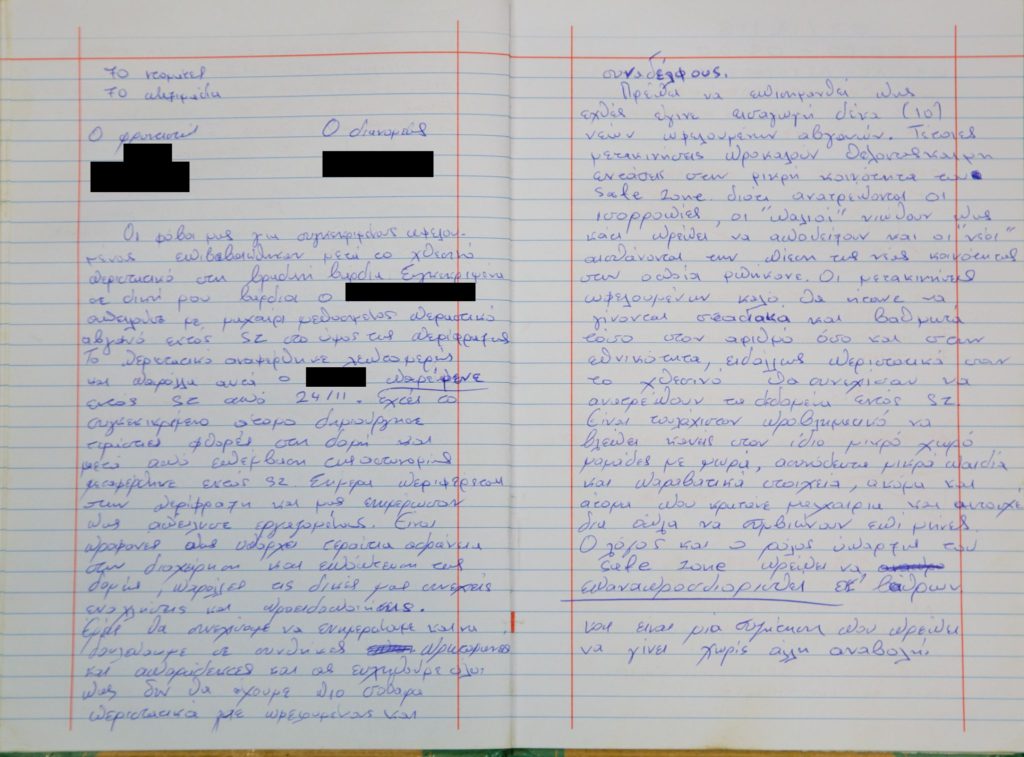

The log of December 7, 2018, is somewhat longer than that of most days, and includes two different kinds of warnings — spanning two pages — from Fanis, the social worker on shift.

Regarding events that took place the previous night — which resulted in police intervention — Fanis writes, “It is obvious that there is a great inactivity in the management and supervision of the section, despite our constant complaints and warnings. We will keep informing and working in unprecedented and unacceptable conditions, and let us all wish that there will not be more serious incidents with beneficiaries and colleagues.”

The care worker goes on to add that ten more Afghan boys were transferred to the safe zone the day before, and warns that transfers of this volume could fuel tensions in the small community of the safe zone.

“The ‘old ones’ feel that they need to prove something, and the ‘newcomers’ feel the pressure of the new society in which they have entered. Transfers of beneficiaries should take place gradually, as their number as well as their nationality matter, otherwise events like that of yesterday will continue to overturn the reality of the safe zone.”

But that is not the only concern the care worker expresses that day. Fanis notes that older boys, involved in acts of violence in the past, appear to remain in the safe zone, causing anxiety to the caregivers. In the logbook, they chronicle encounters with them, and warn of similar events happening in the future.

“In the least, it is problematic to see mothers with babies, unaccompanied young boys and criminal elements, even persons holding knives and makeshift weapons, living together for months in the same place. The role and the cause of existence for the safe zone needs to be redefined and this is a discussion that has to take place with no further delay,” the note concludes.

It appears from the logbook that the competent authorities did not take the required action. Incidents, including violent conflicts between minors, do not stop after this entry, but continue for as long as the book covers.

Answering the questions we asked, IOM stressed that they worked “in close coordination and under the guidance of the Reception and Identification Center (RIC)” which means that the responsibility for any important decisions lies with the Greek authorities. The Ministry of Immigration and Asylum did not respond to any of our questions.

On the day of the last entry — May 8, 2019 — there were 4,752 people living at Moria, even though its capacity at the time was only 3,100. The safe zone had a capacity of about 150 unaccompanied minors but in the time span of the logbook, there were between 300 and 600 living there.

Just three months after that last entry, on the night of August 25, 2019, another incident took place. Just like the care workers had feared, violence erupted. A 15-year-old boy from Afghanistan was stabbed to death in the safe zone.

No provision for unaccompanied minors in Moria 2.0

And now that Moria has burnt to ashes – has the situation for the minor asylum seekers arriving on Lesvos improved?

In the aftermath of the fire, the 400 unaccompanied minors that were then living in the safe zone of Moria were transferred to the mainland. According to the UNHCR, to date seven countries in the European Union have accepted 321 of them.

As new arrivals are happening in Lesvos again, it is unclear at this time where the unaccompanied minors arriving on the island will be accommodated.

The new structure, often referred to as “Moria 2.0”, has been set up in a former shooting range of the Greek army. The people who live there today are only provided with food once a day, and although eight weeks have passed since the camp was created, there are still no showers.

Residents told Reporters United that they have to shower in the open, while parents bathe their children in the nearby sea. The families live in tents, without beds or solid foundation, which were flooded by the season’s first rain storms, while up to 100 single males share big tents, sleeping on bunk beds.

So far, there is no area in which unaccompanied minors can live separately from the rest of the population. As of publication, the Greek ministry has not responded to Solomon’s request for comment.

However, for the time being, in this new reality for the most vulnerable among people seeking refuge in Europe, there isn’t even a “safe zone” anymore.

*The personnel signed the pages of the logbook with their names; most of the time, they used only their first names, but sometimes, they included their last name. The care workers referred to the minors by their full names. Solomon is only publishing the initials of the minors’ first names, and has altered the names of the care workers, in order to protect their privacy.