Editor: Christoforos Kasdaglis

Data analysis and visualisations: Sotiris Sideris, Dafni Karavola, Konstantina Maltepioti

Using advanced data collection and analysis methods, Reporters United tracked the intricacies of the Pillar, a non-performing loans (NPLs) portfolio from Greek bank Eurobank. The investigation was guided by information from the portfolio’s prospectus, dated October 10, 2019, available on the Central Bank of Ireland’s website.

We followed the complex money trail across five corporate groups and 19 corporate structures surrounding the Pillar, headquartered in five countries, including tax havens. Ultimately, the core of this massive web of interrelated ownerships was reached – a core which constantly shifts over time like quicksand, with continuous trading of loans and bonds among them.

This year-long investigation led to crucial conclusions about this exchange, where the identity of owners, shareholders, management, and the business risk-bearing entity disappears in a thick fog of top-level creative accounting.

The goals: tax avoidance, maximising benefits from the “Hercules” securitisation scheme of the Greek state at the expense of the latter, intransparency as to profits and losses, evasion of accountability by companies known to the public –and thus subject to scrutiny– plus obscuring the fact that the fund/company which auctions off people’s properties often becomes the highest bidder and subsequent owner of these properties.

Ultimately, the entire scheme is shown to be meticulously constructed in favour of creditors, and almost always to the detriment of vulnerable borrowers.

The Pillar portfolio consists mainly of mortgage loans valued at approximately €2 billion, originated by Eurobank Ergasias S.A. or by banks acquired by the Eurobank Group. Eurobank is among the four systemic Greek banks. These loans are “secured over (in the majority of cases) residential or other real estate properties located in Greece,” as stated in the prospectus (page 1).

Why does Greece have the highest rate of NPLs in the EU?

In 2019, non-performing residential mortgage loans in Greece accounted for a staggering 44.7% of the country’s GDP, that is €75.4 billion as of June 2019. In 2010 they accounted for 10.3% of the GDP.

But how did Greek banks, including Eurobank, end up with such a mountain of NPLs that have now to a great extent been securitised and sold to funds, resulting in borrowers massively losing their properties?

The story starts back in the 90s, when the residential mortgage market in Greece was rapidly deregulated. As Greece joined the Eurozone in 2000, the country’s credit rating improved and interest rates decreased significantly to the EU average. Consequently, bank lending skyrocketed. Thus, from 1999 to 2009, mortgage loans increased from 5.8% to 33.9% of the GDP. At the end of 2008, they accounted for most of the total household bank debt (€79.14 billion out of 118.47 billion in 2009).

Τhis staggering increase led to uncontrollable levels of debt for the Greek economy, which intersected with the fiscal deadlocks of the Greek state at the end of the decade, studies suggest.

Then, the financial crisis erupted. In 2010, financial rating agencies stamped Greek bonds as “junk.” To avoid default, Greece resorted to the IMF for a bailout, which was received on tremendous austerity terms.

This austerity created deep, and still open scars. Between 2008 and 2013, the Greek GDP declined by nearly 25%. As fiscal adjustment was largely enforced through increased tax burdens, households’ disposable income decreased by about a third. Unemployment skyrocketed from 7% in 2008 to over 27% in 2013, and poverty to 44.3% in 2013 if measured in terms of real purchasing power. “Such a dramatic deterioration in living conditions over such a short period has not been experienced by any OECD-developed country during the post-war period,” research institute Dianeosis noted in a report.

Under these conditions, Greek borrowers increasingly struggled to repay their loans. Non-performing residential mortgage loans quadrupled within nine years.

In this context, the Hercules scheme was launched in 2019, aiming at assisting banks in securitising NPLs and moving them off their balance-sheets. After converting NPLs into securities, banks sell them to investors through a special entity created for this purpose.

As Reporters United documented in a previous report, Hercules was followed by a sharp increase in foreclosures from 2021 onwards. Credit Servicing Firms (henceforth ‘Servicers’ – companies responsible for the daily management of securitised loans) played a vital role in this, as Greece’s Supreme Court decided they can carry out auctions on behalf of funds. Plus, the so-called ‘Katselis’s Law,’ which exempted the borrower’s primary residence from liquidation, was gradually eroded over the crisis years. The New Bankruptcy Code, enacted in 2020, dealt the final blow to it. Indebted citizens can now lose their only home to funds.

Since its 2019 launch, the cumulative state guarantees from three expansions of the Hercules program are estimated at nearly €23 billion. This support has resulted in a reduction of the banks’ NPLs from 40.6% in December 2019 to just above 5% by September 2024. Meanwhile, in March 2023, Eurostat decided that the state guarantees under Hercules I & II, which have not yet been triggered, would not be added to public debt.

The Pillar web

Let us now go through the complex web surrounding Eurobank’s Pillar portfolio.

On June 18, 2019, Pillar Finance Designated Company (Pillar Finance DAC) issued the entire bond portfolio for Pillar (prospectus, p. 1). The notes are listed on the main securities market of Euronext Dublin, which is the primary Irish stock exchange, supervised by the Central Bank of Ireland.

Pillar Finance DAC is a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), established by Wilmington Trust SP (Dublin) Limited in Ireland on 16 February 2018, and headquartered in Dublin. It serves as the core entity in the transactional operations around the Pillar portfolio by issuing the bonds and assigning various roles within the intricate structure.

Through the Hercules scheme, the Greek state has guaranteed the repayment to Class A noteholders (see below) up to €19.2 billion if the amount collected from auctions and other settlements is insufficient. These guarantees are the “big incentive” for funds to buy loans from Greek banks, as noted by Professor Emilios Avgouleas, an expert in International Banking Law and Finance at the University of Edinburgh, in an interview with Reporters United. For this guarantee, the state collects a fee as per market standards.

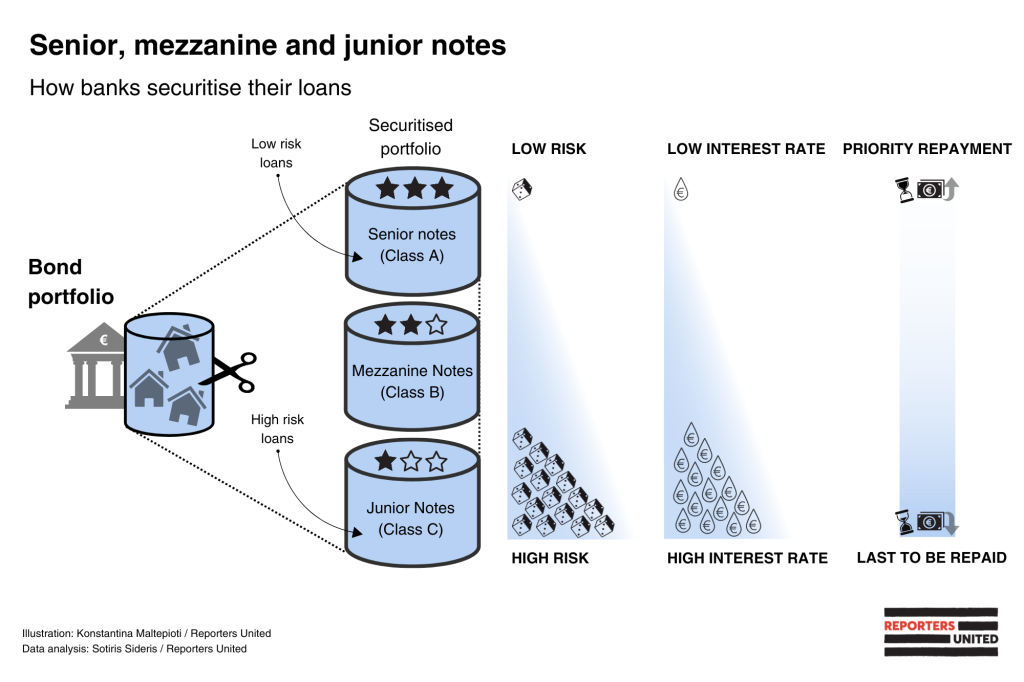

On the first day of issuance, Eurobank purchased 100% of the notes across all classes, including their initial capital – that is, Class A (Senior), Class B (Mezzanine), and Class C (Junior) Notes (for the initial principal balance of each class, see prospectus, p. 1).

Class A Notes come with privileges as they are prioritised for repayment and carry the lowest risk and interest rate. Class B Notes have a higher risk and interest rate, while Class C Notes carry the highest risk and interest rate.

In September 2019, the global investment management firm Pimco headquartered in California (USA) and managing some $2 trillion in assets- through its subsidiary Celidoria, acquired from Eurobank, for €102.5 million, 95% of the mezzanine and junior notes of the Pillar securitisation NPLs. Eurobank retained 5% of these notes and 100% of the senior ones.

By selling the largest share of mezzanine and junior notes, the corresponding ‘bad debt’ is removed from a bank’s balance sheet, studies highlight – and their finances appear healthier. This is, after all, the purpose of Hercules. According to Eurobank’s financial statements, upon completion of this transaction, Eurobank Holdings “ceased to control the SPV” and “de-recognized the underlying loan portfolio in its entirety, on the basis that it transferred substantially all risk and rewards of the underlying loan portfolio’s ownership.”

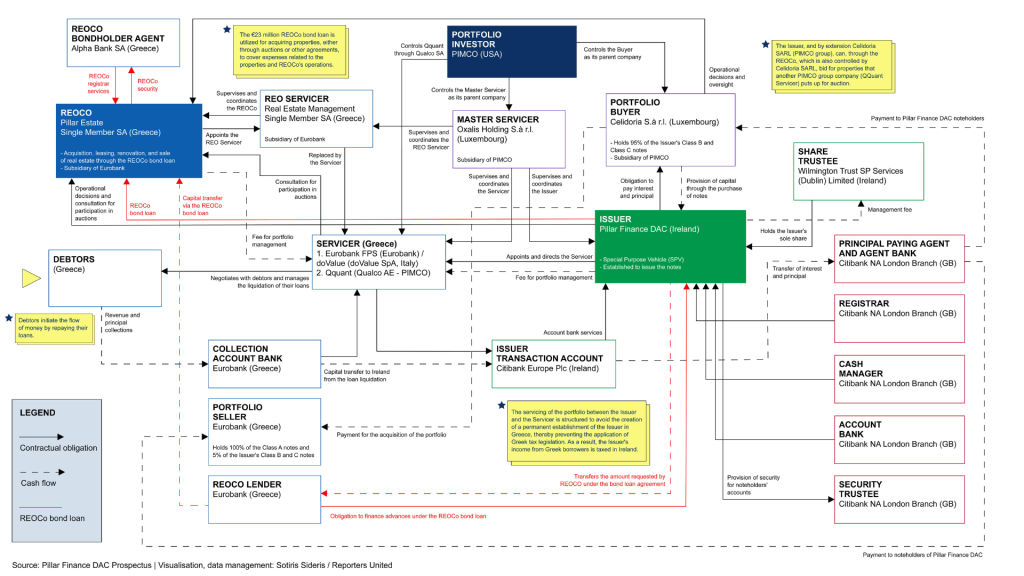

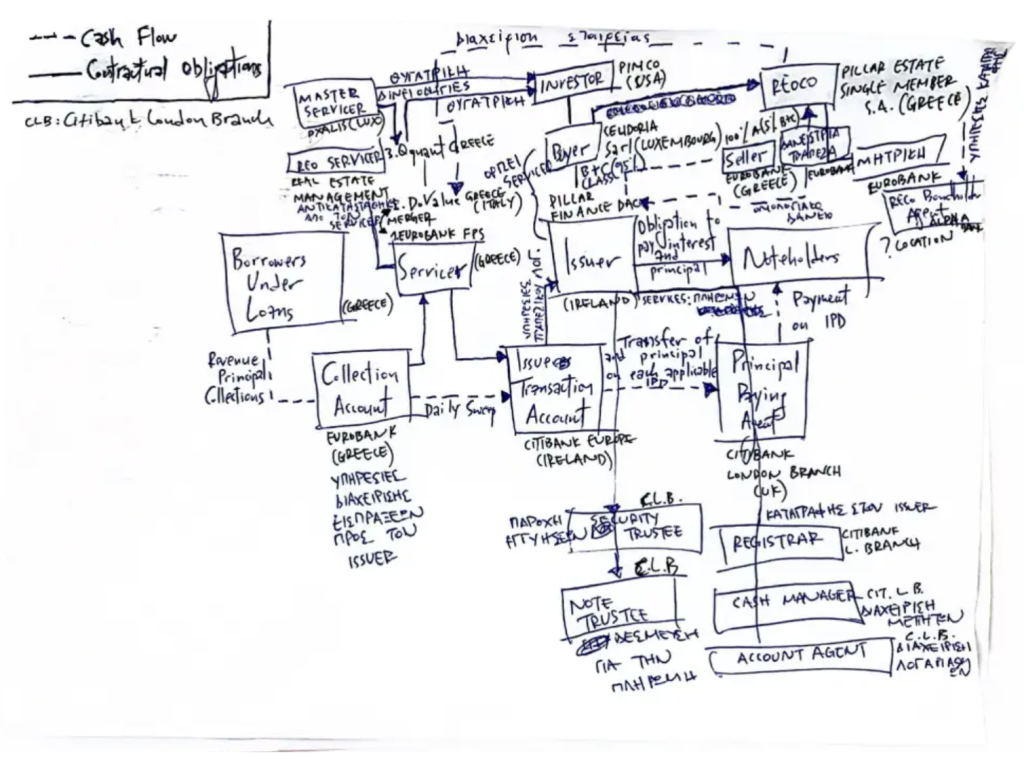

The following diagram illustrates how the web of companies surrounding the Pillar portfolio branches out:

Let us now look more closely into two companies-main players in this report:

>Eurobank FPS Loans and Credits Claim Management S.A., a Eurobank subsidiary, which was the initial servicer. In 2020, it was acquired by –and merged with– doValue, Italian leader servicer in Southern Europe and one of the bad loans’ Big-4 in Greece which acted as the servicer until May 16, 2023, when it was replaced by QQuant, also one of the Big-4.

The main responsibility of the servicer is to manage the loans, conduct portfolio sales and auctions, and provide related services. The servicing of the portfolio by the servicer can be terminated by the issuer (Pillar Finance DAC) and by the security trustee (in this case, Citibank N.A., London Branch).

QQuant is the fourth largest NPL management company in Greece and part of the Qualco group, whose major shareholder is Pimco. It is noted that Pimco, through its subsidiary Celidoria has purchased 95% of the Class B and C Notes – meaning that the same company currently controlling the Pillar portfolio (Pimco via Celidoria) also controls the Pillar servicer (QQuant) through a company of the group in which group it is a major shareholder (Qualco).

>Pillar Estate Single Member S.A. (Pillar Estate), which is a Real Estate Owned Company – henceforth, REOCo. REOCos are established as limited-purpose entities, whose main activities are to acquire and manage real estate assets either already included in the securitised portfolio or expected to be repossessed, according to S&P Global.

When the institution managing the loan, for example the servicer, cannot sell a default property in a short sale or at an auction, the property becomes Real Estate Owned (REO), meaning it is now owned by the creditor/servicer. For this reason, REO assets are also referred to as “bank-owned homes.”

Pillar Estate (the REOCo) was established on June 7, 2019, just eleven days before the Pillar portfolio notes were issued by Pillar Finance DAC. The initial share capital of Pillar Estate was €25,000. Its purpose is to operate in the real estate market. Eurobank Ergasias Services and Holdings SA (Eurobank Holdings) is its sole shareholder owning 100% of its shares. However, according to Pillar Estate financial statements, Eurobank Holdings, “can no longer influence the core activities of Pillar Estate, precisely because of the sale of 95% of the mezzanine and junior notes of Pillar Finance DAC to Celidoria SARL, an entity controlled by the global investment management company Pimco.”

Headquarters in Ireland, assets in Greece

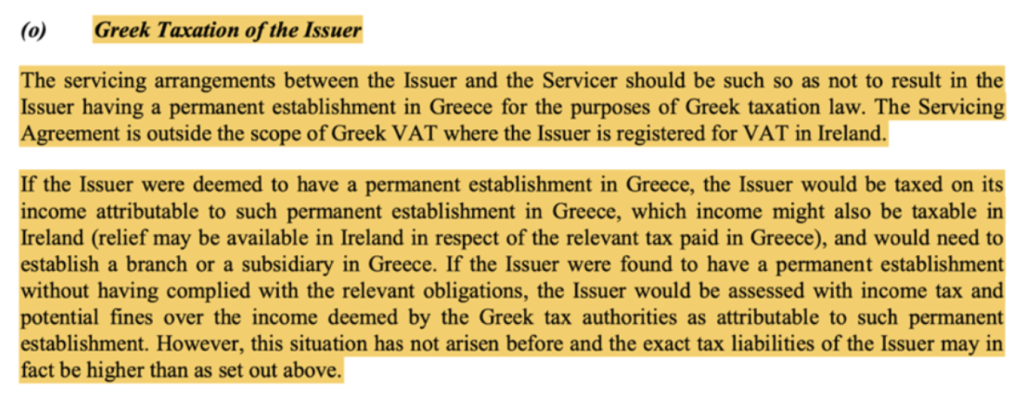

It is common for SPVs to choose a “friendly tax residence” as advertised in the prospectus (p. 51). They often chose this tax residence to be in Ireland. According to Professor Augouleas, SPVs are created primarily “for reasons of bankruptcy remoteness, meaning that should there be claims from fund creditors, they would not be directed towards the fund but towards the SPV, which has its own legal personality and it is supposed to be independent from the fund… This is an old technique; it wasn’t created exclusively for Greece. It was widely used in the US before the recent crisis,” explains the professor. However, “sometimes the SPV is created also for tax evasion purposes.”

Why is the SPV not taxed in Greece? Because, according to Professor Avgouleas, “it is very difficult to prove that the actual headquarters of the fund’s operations is in Greece.” SPVs are part of the shadow banking system, which operates legally. Nevertheless, “we have credit flows that may create investment bubbles and systemic risk along the way, under the very nose of the supervisory authorities.” The shadow banking system preexisted; “that’s why Lehman Brothers collapsed, for example.”

Nikos Stravelakis, economist and visiting lecturer at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, highlights the fact that loan buyers refuse a Greek tax ID as “they try to avoid paying tax on their potential profits.”

Maintaining a tax residence outside Greece means that the revenues of these companies in Greece end up being taxed where the companies maintain a tax residence – in this case, in Ireland. They therefore bolster the Irish economy as, even if tax there is minimal or null, they create ‘development.’

The sums of money offshored are enormous: The total value of the loans being managed by the servicers at the end of the second quarter of 2024 was €69.7 billion, according to the Bank of Greece (BoG’s latest Financial Stability reports in English here). Of these, mortgage loans amounted to circa €21.9 billion.

We discovered the winner of the auctions!

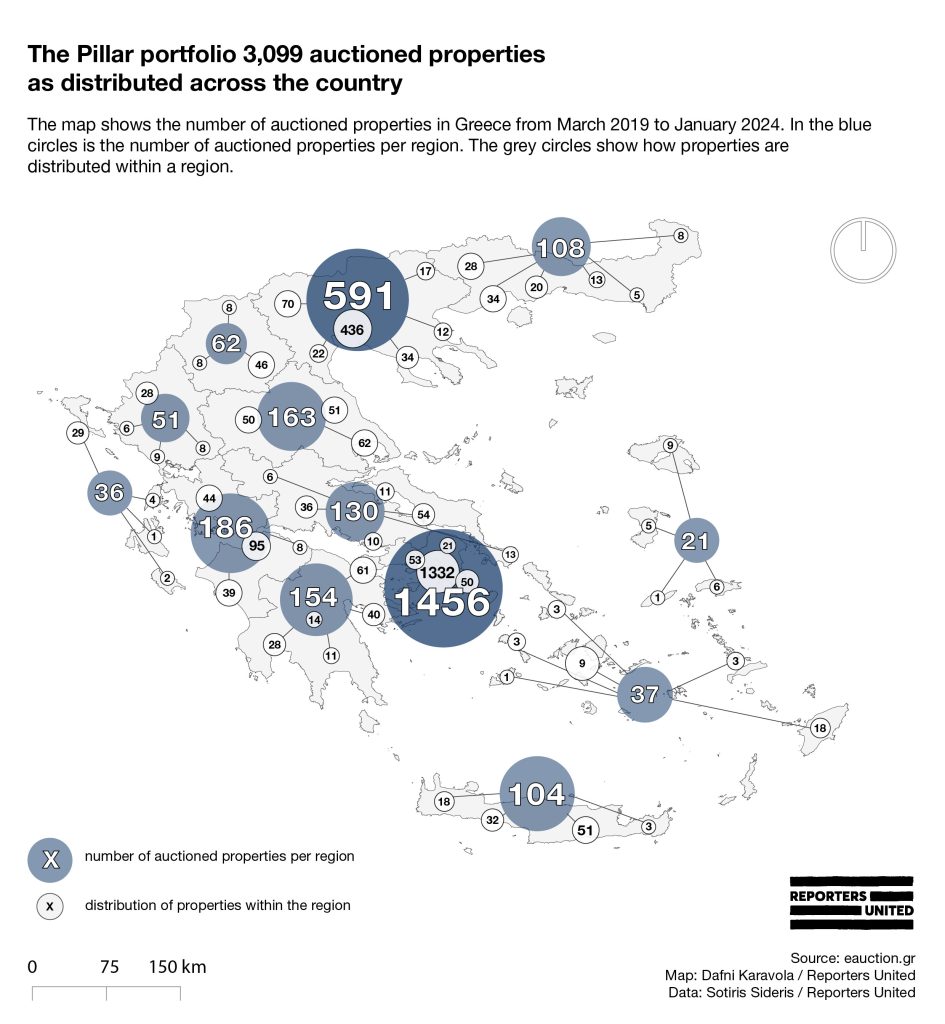

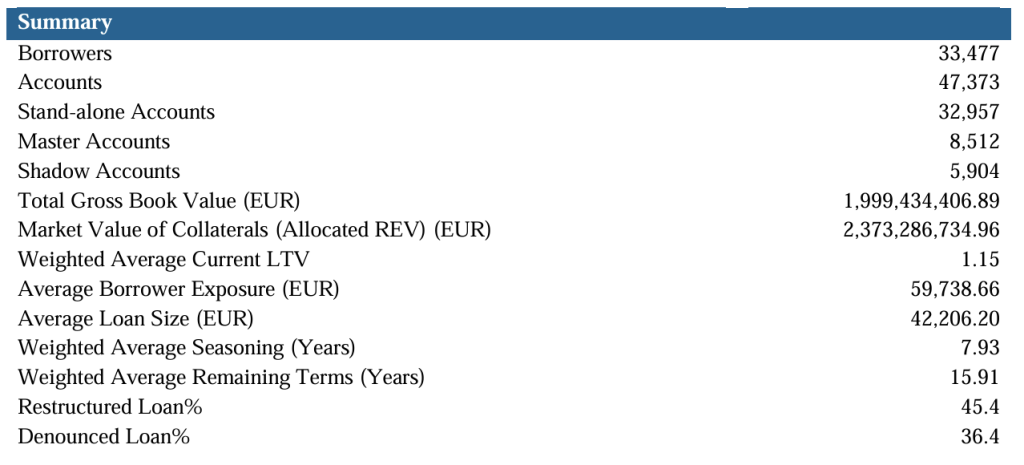

The Pillar portfolio in its initial composition involved 33,477 borrowers, individuals and legal entities. Each borrower has an average debt of €60,000. The total gross value of the portfolio, that is the total sum of the initial loans it includes, is €2 billion (€1,999,434,406.89).The lion’s share (50%) of the property value, corresponding to 40.7% of the portfolio’s loans, is located in the greater Athens area.

We collected and analysed data from the official electronic auction platform of the Greek state, eauction.gr, from March 2019 to January 2024 – for the entire country. Then, we singled out and analysed all entries related to the Pillar portfolio.

During the aforementioned period, 4,820 auctions were conducted by doValue, QQuant, and Eurobank. Of these, 3,099 pertain to unique properties. In other words, the mortgaged properties that have gone up for auction are 3,099, though some of them were auctioned more than once, which is why the total number of auctions is higher.

The vast majority of auctioned properties from the Pillar portfolio are residential, smaller than 90 square metres, over 40 years old, and mostly located in Attica. More specifically, their average size is 80 square metres, and their average age is 42 years.

After analysing these data, one last, and most difficult, step remained:

To discover into whose hands the properties of struggling households are ending up.

We completed this final mile of the investigation by cross-referencing each auctioned property in the Pillar portfolio in the last five years with the only database that provides the necessary information in most cases: the Hellenic Land Registry.

The result was revealing.

Property auctions: Eurobank parties. Drinks are on Pillar

From the 3,099 properties in the Pillar portfolio, 405 (13%) were transferred to new owners. In other words, the auction was successfully completed, and the property changed hands.

Reporters United investigation into the Hellenic Land Registry identified detailed ownership data (name and tax identification number of the new owner, purchase date, etc.) for 243 of the 405 properties that changed hands. For the remaining 162 properties, information could not be found, either because they were not listed in the Land Registry (it is not yet completed in Greece) or due to incorrect registration codes listed in e-auction.gr.

In response to a related question by Reporters United, Eurobank ultimately confirmed that a larger number of horizontal properties (426) changed hands compared to the number identified in our investigation (405), which may be due to the fact that Reporters United stopped collecting data in January 2024 – while the bank’s data extended from March 2019 to March 2024 (All Eurobank responses can be found here – in Greek.)

What Reporters United discovered, however, is that the largest buyer is Pillar Estate, which acquired 41 of these properties, that is 1/6 of the total – twenty seven of them, residential. It remains unclear whether and how it acquired some (if any) of the remaining 162 properties, as relevant data were not found.

The vast majority of these properties (34 out of 41) were auctioned only once, meaning that Pillar acquired them the first time they were auctioned. Five of the 41 properties were auctioned twice, while two were auctioned four times before being ultimately purchased by Pillar.

For 37 of the 41 properties purchased, Pillar Estate bid just one euro above the starting price in the auction, and for one property, just €1.67 above the starting price. These data confirm Reportes United information -obtained by a citizens’ movement against auctions- that if a property is awarded at the starting price, or just above it, it has been acquired by the bank or the fund-NPLs investor who are holding it as collateral.

For the remaining three properties, the hammer price is not available because they were auctioned earlier, when the award amount was not listed on the platform.

In their replies to Reporters United, Eurobank called upon its latest data to clarify that Pillar Estate has bought 62 of the auctioned properties (All Eurobank replies, here – in Greek). The bank claimed that Pillar acquired them “because there was no demand from third-party buyers at that time.”

Eurobank verified a higher number of properties ending up with Pillar Estate than the number our investigation had detected (62 instead of 41), which could be because we managed to collect information for only 243 out of 405 properties for reasons explained earlier.

We also sent questions to the Bank of Greece (BoG). Their responses were rather vague for most of the queries. For example, they responded that “specific measures are taken to prevent conflict of interest during the management of NPLs and the disposal of properties.” (All BoG here – in Greek.)

The Ministry of Finance and QQuant did not respond to our questions.

The fact that Eurobank saw fit to respond, while QQuant conspicuously ignored us, confirms our investigation’s finding that a main objective of this complex structure is to shift the “political” risk of property disposals onto entities that are not susceptible to social pressure. Through Reporters United investigation and questions, the pressure was redirected where it should have been applied in the first place.

Eurobank: An owner without property

A number of properties were acquired by Pillar Estate. That’s a fact.

But who is really behind this company? In other words, who now owns these properties?

As mentioned earlier, Pillar Estate (the REOCo) was established on 7 June 2019, with an initial capital of €25,000 and the purpose of engaging in the real estate market. The company’s shares are 100% owned by Eurobank Ergasias Services and Holdings S.A.— Eurobank Holdings.

At this point, a telling ‘detail’ arises: According to the financial statements of Pillar Estate, “Eurobank Holdings cannot, however, influence the core activities of the company. The reason is that in September 2019, the sale of 95% of the mezzanine and junior notes of Pillar Finance DAC was completed to Celidoria SARL, an entity controlled by the global investment management firm Pimco.” It further adds: “Upon completion of the transaction in September 2019, Eurobank Group ceased to control the company and stopped consolidating it [note: consolidation of financial statements is the accounting method by which the financial statements of a parent company and its subsidiaries are presented as if they were one entity. They are presented as one by integrating the assets, revenues, expenses, and cash flows of the respective consolidated companies into the parent company’s financial statements], transferring all benefits and risks to Celidoria SARL, as Eurobank Group no longer holds any voting rights or contractual rights which would enable it to direct the relevant investor’s operations.

The Eurobank Group cannot exercise control over the REO Servicer, who makes all critical operational decisions for the Company regarding the conduct of its activities, nor can it influence the company’s plans and policies that shape its cash flows.”

Simply put, it is stated that Eurobank Holdings, although the sole shareholder of Pillar Estate, and despite the fact that the group continues to hold the Class A Notes of the Pillar portfolio, does not control the company that was established to acquire Pillar properties through auctions.

This raises a critical question with interesting implications: How is it possible for Pillar Estate to be controlled by Celidoria-Pimco while being a sister company of Eurobank, and Eurobank Holdings is its sole shareholder?

Note that, while the Hercules scheme is based on distancing the creditor bank from non-performing loans and the fate of the properties, in their aforementioned replies to Reporters United, the bank does not claim it is no longer related to these properties—and thus the profits or losses resulting from their auctions—but instead provides information about their status, implicitly acknowledging its involvement. It is also noteworthy that in their replies, the bank refers to itself as a “senior noteholder,” indicating its continued connection to the entire arrangement. This confirms our investigation’s conclusion that the bank enjoys all privileges stemming from this “distancing” through a nominal structure that allows it to retain the umbilical cord and benefit from the distribution of capital gains that arise by having set itself in advantageous position.

Because all this amounted somehow to higher mathematics, Reporters United had to turn again to the insights of Nikos Stravelakis. “It’s an entire game where all the banks try to somehow separate management from control. Since junior notes might have been sold at a very low price, to avoid recording the loss, they conducted an accounting maneuver: the bank does not appear as the seller of the loans; instead, a holding company that is the bank’s parent [i.e., Eurobank Holdings, which is listed on the Athens Stock Exchange] appears as the seller. This way, any loss is passed on to the holding company, and the bank’s capital adequacy is not affected.”

Step 1: Setting up a chain of companies

The junior notes with an initial principal balance of €645,398,000 were issued by Pillar Finance DAC at €1 (prospectus, p. 1), in June 2019.

In 2020, Eurobank Ergasias S.A. was renamed Eurobank Holdings while at the same time a new corporate entity was created, Eurobank S.A., a 100% subsidiary of Eurobank Holdings. According to its website, Eurobank Holdings retains operations and assets that are not related to the main banking activity, but rather focus on the strategic planning of NPLs management and the provision of services to the group’s subsidiaries and third parties.

They have also performed a second accounting maneuver, however, according to Mr. Stravelakis: “By using a very refined provision of international accounting standards, which states that if I don’t have control, I don’t have to consolidate [the financial statements of the subsidiary with the parent company], they stopped consolidating the company within Holdings. This way, if they sold the loans to Pimco for peanuts, they don’t record the loss because they no longer consolidate the company. Therefore, they retain a participation that is worth 100, which they display at its acquisition value of 100, without showing the changes in the company’s net worth, meaning the company’s equity. Essentially, this way, they might be hiding losses.”

“The third issue is that Eurobank remains a shareholder. This means they transferred the assets and remained a shareholder without recording the results of this trade! Neither the profit nor the loss.”

Mr. Stravelakis believes that this could all be happening “to cover up the fact that the entity auctioning the property is also the highest bidder!”

Thus, “if tomorrow morning I put your house on auction and buy it for a pittance, I’m not to blame; Pimco or whoever is managing Pillar is. Because I no longer make any decisions — I’m an innocent party, a third party. Of course, there’s one small detail: all the shares are still mine. Also, I might record profits or losses, but I didn’t make the decisions.”

Ultimately, if Eurobank Holdings were to conventionally transfer all of Pillar Estate’s shareholder rights (but not the shares) to Celidoria, then why go through the process of establishing the company in the first place, if not for the reason described by Mr. Stravelakis?

Step 2: Fudging profits and losses

Meanwhile, Pillar Estate appears to be operating at a loss. According to its financial statements, the company’s net pre-tax results in 2021 showed losses of €657,822. In 2020, the losses were €361,482.

By 2021, its total equity (its net worth after subtracting loans and liabilities) was negative, by €1,026,548. In 2020, it was also negative, by €358,396.

How is it possible for a company with an initial share capital of just €25,000 to have purchased (at least) 41 properties according to our research, 62 according to Eurobank’s responses, within just four and a half years after its establishment, while recording such significant and growing losses in both its net results and equity? Shouldn’t it have gone bankrupt?

Step 3: Questionable borrowing

According to its 2021 financial statements, the company “does not face liquidity problems because, with the Bond Loan it has secured, it can cover, among other things, all general expenses related to its operations, as well as its obligations towards the Greek state and all its suppliers.”

The total Bond Loan amounted to €23,000,000, with €6,735,000 disbursed by April 20, 2023.

Who would lend such an enormous amount to a company with an initial capital of €25,000 that is also recording losses and negative equity? “No normal lender,” concludes Mr. Stravelakis.

In the Pillar prospectus (p. 194), it was noted that the REOCo “will use the proceeds from the REOCo Bond Loans to (a) bid for a Property at auctions or purchase a Property as part of an Amicable Settlement…”

In Pillar Estate 2021 financial statements, it is mentioned that when the company “requests any amount under the Bond Loan, Pillar Finance DAC is obliged to transfer the corresponding amount to the lending bank (‘Eurobank’ or ‘the Bank’) so that the latter can disburse it to the company (…) The Bond Loan is not financed by the Bank but by the Reserve Account registered with Pillar Finance DAC.”

However, Pillar Finance DAC has sold 100% of the Pillar portfolio notes to Eurobank and Celidoria-Pimco. So, by whom and why is the “Reserve Account” funded?

“What does ‘Reserve Account’ even mean?” Mr. Stravelakis wonders. “It’s all legal dribbling in order to hide behind grandiose terms what’s really happening… They’ve set up 3-4 companies, so that the market would become ‘internal.’ It’s a network of transactions through which they essentially aim to take possession of people’s properties. If there’s profit, they won’t pay tax, but if there’s a loss, we’ll pay for it.”

Who, then, granted the loan?

In the 2019 financial statements of Irish-based Pillar Finance DAC (p. 2), it is stated: “Eurobank Ergasias S.A., as Loans and REOCo Bond Provider, granted to the Company a Loan and REOCO Bonds Receivable and the proceeds of the Loans are used to fund the Cash Reserve established and maintained on the Cash Reserve Account.”

This means that Eurobank has lent to the subsidiary it no longer consolidates, says Mr. Stravelakis. He emphasises that “if Eurobank granted a loan to itself, it must explain the purpose of this transaction, given that it runs a double risk on these loans, and this is in direct contradiction to the goals of the Hercules program. Because the purpose of Hercules, at least its declared one, was that ‘the banks would sell some securitised loans, and the risk for collecting these loans and paying interest to third parties would be borne by others.’ That is, the risk would permanently and irrevocably be removed from Greek banks.”

Furthermore, international financial regulations stipulate that “when the parent company grant a loan to any subsidiary or associated company (Eurobank Holdings is still connected to Pillar Estate as it holds 100% of its shares), it must have prepared a Transfer Pricing Report, which documents that it provided the loan under the same terms any other lender would have done,” notes Mr. Stravelakis. This is apparently to ensure competition is not distorted.

Reporters United asked Eurobank if it had prepared a Transfer Pricing report. The bank insisted that “it has already been explained in detail that Pillar Estate is not a connected company” and claimed that there is no transfer pricing obligation because the account balance is currently zero. (The full second response from Eurobank is here, in Greek).

To sum up the course of events:

Eurobank Holdings establishes Pillar Estate.

Then, Eurobank Holdings provides a significant loan to the loss-making Pillar Estate, without considering transfer pricing as an issue and without preparing a relevant report.

Finally, it stops consolidating it.

And then, through these accounting maneuvers and internal lending, Pillar Estate acquires a large number of the auctioned properties at prices lower than the market value (effectively setting desirable prices that the market cannot influence—“market cornering”). If the properties are resold, it pockets the capital gains.

Readers can make their own conclusions.

Step 4: Maximising capital gains

How does Pillar Estate, and thus the companies behind it, maximise capital gains? If a mortgaged house is worth €1 million and the debtor owes €200,000, the house will be auctioned for €200,000, maybe a little more, but then the bank or fund will sell it at its market value, which is a million.

The only rational explanation, according to Mr. Stravelakis, is that Eurobank and Pimco created this corporate structure to extract capital gains from the senior tranche properties.

And why didn’t then Pimco buy the senior tranche notes, which are secured? “Probably because it cannot know in advance whether the nominal value of the guarantees [provided by the Greek State] will be at 100% or 65% of the estimated value of the properties,” Mr. Stravelakis assesses, as the debtor might have to repay more creditors.

“However, the lender [of Pillar Estate] has a huge advantage in the definitive and full acquisition of the properties.” On the other hand, Eurobank “appears to have transferred the loans (concealing the risk it assumes), while by pledging Pillar Estate shares, it transfers voting rights and does not consolidate. Thus, Eurobank conceals that it is buying itself part of the collateral-properties it is auctioning.”

Step 5: Pledging of Shares

Mr. Stravelakis believes that Eurobank may have pledged shares of Pillar Estate, transferring voting rights. “However, the company holding the shares as collateral may release the voting rights at the General Assembly, as it has happened in other cases in the past.”

“Overall, it is a non-transparent agreement that obscures who bears the risk of the notes issued in relation to the non-performing loans,” Mr. Stravelakis concludes. In addition, Eurobank has retained the Class A Notes (Eurobank Holdings recognised them on its balance sheet, and in March 2020 they were transferred, ‘among others,’ to Eurobank), thus the bank also takes on their risk.

“This is significant because we do not know if and to what extent the Greek state guarantees are involved. Finally, there is also a tax issue: Who and where will be taxed for any capital gains on Pillar Estate properties?” Mr. Stravelakis concludes.

And who else but the Greek people will be called to recapitalise Eurobank (all four systemic banks have been repeatedly recapitalised by the state during the crisis) if this substantial part of the risk materialises?

Reporters United report caused rifts within Greece’s ruling party

Less than three months after our publication, eleven lawmakers of ruling New Democracy (ND) tabled a parliamentary question on non-performing loans. In a highly unusual move, they emphasised that securitising NPLs and transferring them to funds improved the banks’ balance sheets, but left borrowers unprotected.

The lawmakers called upon the complex web of companies as documented for the first time in Greece in our report, without however explicitly naming the report or Reporters United. They emphasised that “another practice was recently reported and documented.” The fund that purchased the loan puts the borrower’s property up for auction. “The property is acquired at auction by a real estate company with an identical name to the fund that purchased [i.e. securitised] the loan, while [this real estate company is] a single-member S.A. company with sole shareholder the bank which transferred the loan. This way, the bank secures the fund’s profits, which are not taxed in Greece.”

Five days later, ND expelled from its parliamentary group their MP Marios Salmas. Salmas claimed he was expelled mainly because he co-signed this question.

Research Methodology

This is step by step how Reporters United retrieved and managed data that informed this investigation on Eurobank’s Pillar portfolio.

Sketch: Sotiris Sideris.

The research began with the 270-page prospectus of Pillar Finance DAC, obtained from the Central Bank of Ireland website. This document offered crucial insights into the portfolio’s structure and the network of companies involved. To further understand the transactions, we built our own databases by integrating information from various sources.

Next, we collected data on auctioned properties linked to the Pillar portfolio from eauction.gr, cross-referencing these with press reports, Hellenic Land Registry records, financial statements, and interviews. We created structured datasets that formed the basis for our reports.

Decoding the Pillar prospectus and transactions

The Pillar Finance DAC prospectus detailed the issuance of €2 billion in bonds, with payments tied to real estate-secured non-performing loans in Greece. The document also included graphical representations of transaction structures and cash flows, which helped us visualise the relationships between companies involved.

To enhance our understanding, we manually sketched diagrams to identify patterns, which eventually led to the creation of a final digital visualisation.

Data retrieval and analysis from eauction.gr

Reportes United compiled a dataset covering 3,099 auctioned properties between March 12, 2019, and January 13, 2024, using data from eauction.gr. This dataset included auction details such as starting bids, property addresses, and auction award prices. For half of these properties, auction award prices were only marginally higher than initial bids, raising concerns about the auction process.

We used Python and tools like Apache Tika to extract property data and created three datasets: auction details, reports, and property characteristics. These were cleaned using Pandas, Regular Expressions, and OpenRefine.

Mapping the auctioned properties

Using QGIS, we mapped the auctioned properties based on geographic coordinates and categorised them by use (e.g., residential, business). This interactive map was further enhanced with Mapbox, allowing for spatial analysis of property distribution, use, and starting bid prices.

Hellenic Land Registry search: Who is buying the properties?

As eauction.gr does not disclose buyers, Reporters United used the Hellenic Land Registry to identify the buyers of 405 auctioned Pillar properties. We found 41 of the 243 located properties were purchased by Pillar Estate Single Member S.A., though this number may be higher due to incomplete data.

We categorised the buyers into natural and legal persons, focusing on entities like Pillar, Eurobank, and other real estate/investment companies.

Transparency and accessibility

We aim to make Reporters United journalistic investigations transparent and accessible by publishing our data and methodology. This open-access approach supports wider participation in data-driven journalism.

This is the English version of two Reporters United reports, which were originally published in Greek on 27 June and 2 July 2024. This version has been adopted for international readers. It is also shorter than the original reports and updated.

The report is part of the Ghost Debts investigation by the Urban Journalism Network, a cross-border project involving reporters, data journalists, and visualisation experts covering one of the most pressing issues faced by European cities: housing crisis.

The research was funded by Stars4Media and Journalismfund Europe.

Φοβερή δημοσιογραφική έρευνα , εύγε σε όλα τα στελέχη και εργαζόμενους του reporters united.gr