English editor: Georgia Nakou

Data visualisation: Thodoris Chondrogiannos

Read the Greek version of the story, published on February 8, here.

Where do ships go to die? Who kills them, and how? Does it matter how they die? If a ship’s death takes place far away, does its instigator cease to be responsible?

Ships reach the end of their lives when their owner finds it economical to sell them for scrap, in order to recover the value of their constituent materials. However, many of those materials (including asbestos, PCBs and petroleum product residues) can be highly hazardous to handle, and toxic. The EU classifies so-called “end-of-life ships” as toxic waste and prohibits their export except under strict conditions.

When a ship reaches the end of its commercial life, owners are faced with two choices for disposing of them. The less economically attractive option is to dismantle them for recycling in one of 40 EU-approved facilities worldwide located in Europe, Turkey and the US.

The solution which many shipowners find more attractive – but is prohibited under EU Regulation 1257/2013 – is to have the ships broken up on a beach in India, Bangladesh or Pakistan. The owner receives the scrap value for the ships, which are directed to the unregulated scrap yards of South Asia, where they are beached with the help of the tides. What follows is an environmental and humanitarian crime.

For the past decade, the organisation NGO Shipbreaking Platform has been compiling an open source database of unregulated shipbreaking activity, bringing together information from a variety of sources. Its latest report, Toxic Tide 2020, was published in February 2021.

“Whilst some EU Member States are increasingly cracking down on environmental crime, almost a quarter of the tonnage broken in South Asia was owned by European shipping companies. Greece in particular has systematically closed its eyes to the deplorable end-of-life track record of its shipping industry.”

Ingvild Jenssen, Shipbreaking Platform

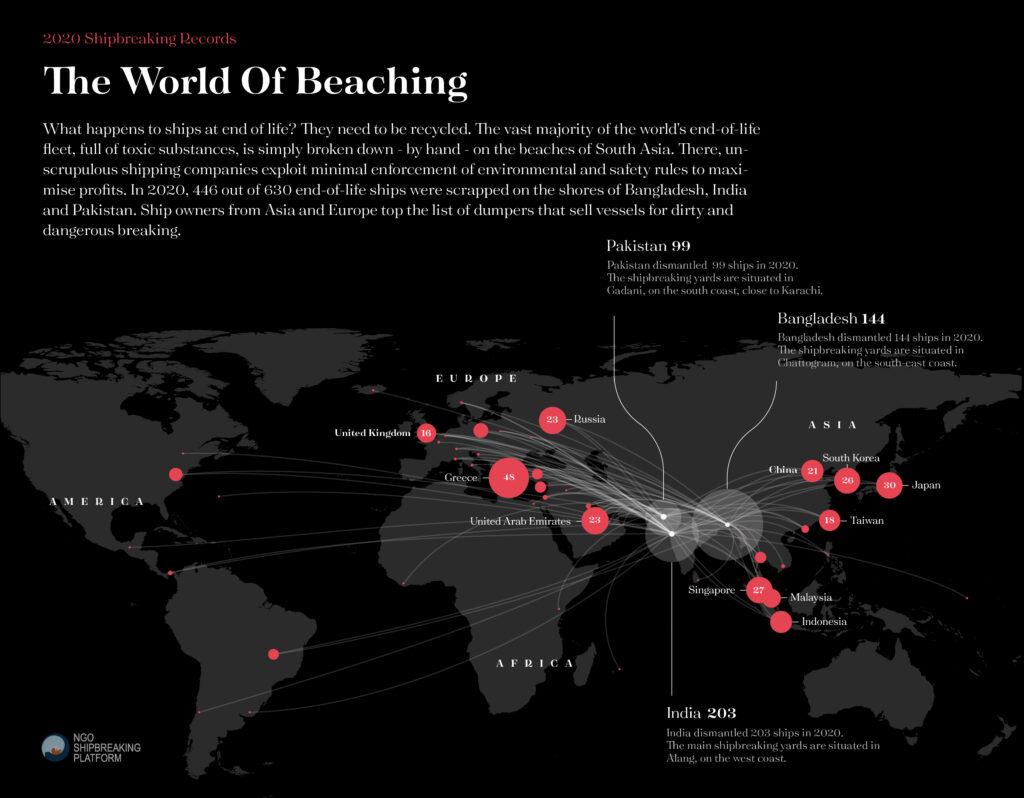

According to the report, 630 ocean-going commercial vessels were sent to the scrap yards in 2020. Of these, 446 large tankers, bulkers, offshore platforms, cargo- and cruise ships were broken down on the beaches of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, amounting to almost 90% of the gross tonnage dismantled globally.

Once again, Greek shipping topped the list, with 48 ships of Greek ownership ending up in the beaching yards of South Asia, making Greece the report’s “top dumper” globally. The next country on the list – by a significant margin – is Japan, with 30 ships. This also marks an increase from 2019, when Greek shipowners sent 40 ships to be scrapped in this manner.

Greece turns a blind eye

“Whilst some EU Member States are increasingly cracking down on environmental crime, almost a quarter of the tonnage broken in South Asia was owned by European shipping companies,” comments Ingvild Jenssen, founder and Executive Director of Shipbreaking Platform. “Greece in particular has systematically closed its eyes to the deplorable end-of-life track record of its shipping industry.”

The Greek merchant fleet is the largest in the world, so perhaps it should come as no surprise that most ships sent for breaking are Greek. This assumption would be justifiable if the South Asia shipbreakers were the only option – but they are not. Several shipowners outside Greece are now turning to EU-approved recycling facilities for dismantling their ships, but the overwhelming majority of Greek companies persist in using this method.

“Only one Greek owner, Interunity, recycled its vessels in a sustainable manner at a ship recycling facility approved under EU law,” Jenssen notes.

It is not only the world of shipping which turns a blind eye to shipbreaking. There is almost no awareness of this facet of the industry in the shipping magnates’ home country, where the majority of the media as well as most relevant environmental organisations remain silent on the subject.

The human cost

Although the problem lies half-way around the world, in Alang, Chattogram and Gadani, it cannot remain hidden. As Shipbreaking Platform put it in their report, “[t]he human costs and the environmental impacts of taking toxic ships apart on the South Asian beaches are devastating. Accidents kill or maim numerous workers each year. Many more workers suffer from occupational diseases, including cancer. Toxic spills and pollution cause irreparable damage to coastal ecosystems and the local communities depending on them.”

In many cases the workers in South Asian beachestake apart the enormous toxic hulls using tools and machinery with their bare hands, while the scrapyards are also notorious users of child labour.

The human impact of this practice has been the subject of extensive studies by international organisations and NGOs. Among them, the 2009 report by the UN Council on Human Rights and the joint report by FIDH (the International Federation for Human Rights) and Greenpeace entitled “End of Life Ships: The Human Cost of Breaking Ships” (2005). The latter estimated that over a period of two decades the human toll including “hidden deaths” – casualties as a result of occupational diseases – could number in the thousands.

The 48 Greek ships

Reporters United has analysed the data gathered by NGO Shipbreaking Platform, and identified a total of 62 ships controlled by Greek interests in the total of 630 in the database. We excluded those dismantled in EU-approved facilities (14 instances, all dismantled at Aliaga on the Turkish coast opposite Lesvos).

This leaves 48 ships, which on the table below are tied not only to the single-ship companies which technically own them (following the common practice of “one ship one company”) but also to the company that is their beneficial owner.

CAPTION: Note by NGO Shipbuilding Platform, endorsed by Reporters United: The data gathered by the NGO Shipbreaking Platform is sourced from different outlets and stakeholders, and is cross-checked whenever possible. The data upon which this information is based is correct to the best of the Platform’s knowledge, and the Platform takes no responsibility for the accuracy of the information provided. The Platform will correct or complete data if any inaccuracy is signalled. All data which has been provided is publicly available and does not reveal any confidential business information.

V.I.P. dumpers

Among the ships dismantled on the beaches of South Asia in 2020, we identified ships associated with a number of prominent Greek shipowners. They include:

- The Crassier, dismantled in Alang, India, previously owned by Golden Union Maritime, a company controlled by Theodore Veniamis, president of the Union of Greek Shipowners;

- Five ships dismantled in India, previously owned by Costamare Inc., which is controlled by the Constantakopoulos family, also known for their investment in the Costa Navarino resort near Pylos;

- Two ships broken up in Bangladesh, previously owned by the Angelicoussis Shipping Group, which is controlled by the billionaire John Angelicoussis, believed to be Greece’s wealthiest shipowner;

- The tanker Rino, dismantled in Chattogram, Bangladesh, previously owned by Navigator Tankers Management, controlled by the Vardinoyiannis family, one of Greece’s most powerful business groups;

- The reefer Skyfrost, also broken up in Chattogram, previously owned by Lavinia Corp, a Laskaridis family company (the Laskaridis family are the subject of a separate Reporters United investigation);

- The list also includes ships controlled by Anna Angelicoussis (sister of John), John Dragnis, Nikos Pateras and Adamantios Polemis.

Orpheus’ Lyra

Among the shipowners on the list, we identified two members of the board of the environmental organisation HELMEPA, which is funded exclusively by the Greek shipping community.

The President of HELMEPA’s Board of Directors since 2020 is Semiramis Paliou, who also happens to be Deputy CEO of Diana Shipping, a NYSE listed company. Up until February 2020, Diana Shipping owned the ship Norfolk – which was renamed the Orpheus shortly before being dismantled in Bangladesh. However, the company – which to its credit was the only one which responded to our questions – claims it had no knowledge that the ship would end up at a South Asian beach yard.

In an email to Reporters United, Diana Shipping states that the Norfolk was “sold for further trading to an unaffiliated third party” (as distinct from being sold for scrap).

We asked Diana Shipping for the name of the buyer, as they were not named in the press release announcing the sale. The company named the buyer as Lyra Trading Limited. Lyra Trading is a company with no ships or shipping activity. It does, however, have a long track record of shipbreaking leading up to its acquisition of the Norfolk. The Equasis database of shipping data includes at least nine ships which were sold to Lyra immediately prior to being sent to South Asia to be scrapped.

Commenting on the stance of the Greek shipping company, a representative of NGO Shipbreaking Platform stated the following: “It is hard to believe Diana Shipping when they claim that they were unaware of the final destination of the vessel. Companies have a duty of care and responsibility to ensure that their operations follow environmental law, also within their supply-chain. Due diligence when selecting business partners is part and parcel of that responsibility. A simple background check would have revealed the identity of the buyer: a paper company based in Liberia with no active fleet, which happens to be linked with recent deadly scrap sales to the worst yards on South Asian beaches.”.

Another member of the HELMEPA board is Aristeidis Pittas, Managing Director of Eurobulk, another company in Shipbreaking Platforms “top dumpers”. Four of the company’s ships were sent to South Asia to be broken up in 2020.

In spite of these findings, our exchanges with Diana Shipping contain a ray of hope suggesting that practices may be changing in some quarters of Greek shipping, as we shall see below.

The death of Mizanur Rahman

Shipbreaking Platform’s Jenssen observes: “Whilst HELMEPA sponsors beach clean-ups in Greece, many of its members are unscrupulously polluting and exposing workers to toxics on the beaches of South Asia. At least one worker died last year taking apart a Greek vessel.”

The incident Jenssen refers to took place in February 2020 in Bangladesh. Mizanur Rahman, 22, lost his life while dismantling the shop Anangel Haili. He had been working at the beaching yard just four days when he died. Prior to being dismantled, the ship belonged to the Angelicoussis Group. Reporters United contacted the Angelicoussis Group with a number of questions, but had received no response at the time of publication.

The role of cash buyers

Can a Greek shipping company be held responsible for something that happened to its ship after it was sold for scrap? Shipping companies generally sell their end-of-life ships to cash buyers – that is, companies who buy the ships at scrap value and arrange for them to be dismantled. Cash buyers will often change the flag and the name of the vessel in order to make it harder to trace to the seller. In this way, shipping companies can avoid incurring any potential legal liability for deaths, injuries and chronic illnesses among workers in the shipbreakers, and claim plausible deniability for what happens on the beaches of South Asia.

While EU law prohibits the dismantling of ships in South Asia, the legislation only applies to ships sailing under the flag of an EU member state. Most of the Greek shipowners who send their ships to South Asia already make use of “flags of convenience” in order to remain outside the jurisdiction of the EU.

Even for ships sailing under an EU flag there is a way to evade EU law, and that is to change flags just before dismantling. The Angelicoussis Group, for example, bucks the trend among Greek shipowners by using the Greek flag on its ships while they are commercially active. However, we can see that in December 2020 a ship from the Angelicoussis fleet, the MARAN GEMINI, switched from a Greek flag to that of the Marshall Islands, shortly before being sent to Chattogram in Bangladesh for dismantling. This way, the original owners avoided being subject to the EU Regulation on recycling of ships.

Silence from the Union of Greek Shipowners

Reporters United approached the Union of Greek Shipowners, whose membership includes a number of the companies on the Shipbreaking Platforms database, with questions relating to this article. At the time of publication, we had not received a response.

We also addressed questions to the Angelicoussis Group, the Vardinogiannis family group, the Constantakopoulos group, Diana and Eurobulk, as well as HELMEPA.

Costamare, owned by the Constantacopoulos family, included the following in its response: “Costamare is a company listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and is bound by very strict rules and standards which concern – inter alia – transparency, corporate governance and responsible business conduct. […] In relation to the environment, our company’s commitment is continuous and unwavering, and is enshrined in its environmental policy, as part of which we have adopted a comprehensive Environmental Management System. […] [E]nvironmental issues are addressed as part of Costamare’s core activities, ensuring that the company’s policies on sustainability form an inextricable part of its activities”.

In its response, HELMEPA noted:

“The Hellenic Marine Environment Protection Association (HELMEPA) […] has for a number of years addressed in its education programmes for officers and executives in its member companies the issue of safe and environmentally-friendly dismantling of ships. In addition, in our capacity as Technical Advisor to the Greek representation on the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), HELMEPA […] contributed to the drafting of the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, and supports along with other international shipping organisations its accelerated implementation”.

The responses in full from Diana Shipping, Costamare and HELMEPA can be found here. At the time of publication we had not received a response from the Angelicoussis and Vardinogiannis groups, and Eurobulk.

A ray of hope

In our exchanges with Diana Shipping regarding the dismantling of the Norfolk/Orfeus, while we did not find the company’s explanation particularly persuasive, we do see in it some potential signs of progress. Semiramis Paliou, to whom we addressed our questions, was appointed deputy CEO of the company at the end of 2019, and President of the Board of HELMEPA in mid-2020, making her one of the new generation of Greek shipping.

Sources within Diana told Reporters United that the practice of shipbreaking on the beaches of South Asia is “problematic”, and that it must cease. “There is no turning back on this issue, the most important step is not to simply obey the law but to change our culture”. The same sources informed us that Diana’s next ESG (Environmental & Social Governance) report will for the first time contain extensive environmental commitments. Whether the company are indeed “true believers” in these commitments – as our sources put it – will become apparent in time. However, such initiatives offer a ray of hope, at a time when Greece’s largest shipping companies are stubbornly in denial on this crucial issue.

“Clean and safe ship recycling is possible. We encourage Diana Shipping to adopt a sustainable policy that bans the use of the shores of South Asia as dumping ground of their ships”, comments a spokesperson for Shipbreaking Platform.

Would we let this happen in Greece?

Paraphrasing an earlier campaign by the organisation, Shipbreaking Platform’s Ingvild Jenssen told Reporters United, “It would never be allowed to operate a heavy and hazardous industry on the beaches of Greece.”

The question for the Greek shipping industry is more timely than ever: Would the Greek shipowners who send their ships to be dismantled at Alang, Chattogram and Gadani allow something like that to happen on the beaches of the Cycladic islands, Crete, or Pylos?