Editing: Georgia Nakou

Data visualisation: Konstantina Maltepioti

“Name your three favourite places in Greece, then look at the map of the Greek Energy Regulator. There is most probably a wind farm planned there”, says Dimitris Gotsis, a design engineer and outdoors activities guide from the Peloponnese, who is spending his days and nights researching planned wind farms in Greece.

Wind turbines at an elevation between 1,700 and 2,000 metres on a mountain range so unspoilt that its name is Agrafa (meaning “blank slate”). Wind turbines along the entire spine of the island of Amorgos, where the Luc Besson movie “Le Grand Bleu” was filmed. Wind turbines on 23 protected islets of the Aegean, prized as invaluable bird sanctuaries due to the complete lack of human footprint. On the island of Andros, a hiking paradise, enough wind power to cover the needs of the island almost ten times over. On the mountain of Oiti, a wind farm inside the National Park. Wind turbines on 80% of the peaks of Pindos, the mountain range that runs through the entire Greek mainland.

These are among the approximately 9,000 new turbines that are in the advanced stages of the process to obtain permits, or the approximately 7,000 turbines at the initial assessment stage by the Greek authorities. The average output of the individual planned turbines is almost 3 ΜW and their average height is 150 metres, while some reach 250 metres at the tip of the blade (the Eiffel tower is 300 metres high). This is in addition to the 2,500 turbines that have been installed over the past few years, at a total installed capacity of 4.34 GW. Production from all turbines currently seeking permission exceeds even the most ambitious green transition goals and is also totally unrealistic given the constraints of the grid. Nevertheless, every couple of months, hundreds of new applications are being submitted.

Wind power companies say there is nothing to worry about.“Only a small percentage of applications lead to the construction of actual wind farms” points out Panagiotis Papastamatiou, CEO of the Hellenic Wind Energy Association, the industry lobby group. “We are in favour of strict selection.”

As of February 2021, wind farm projects totaling 30.49GW have paid the required fees and have a production permit. The environment ministry has recently offered developers the option to return the permit and get their money back, a process that might help clear the field, weeding out around 20% of projects, according to industry estimates. Yet more applications might fail to secure the funding guarantees required by the new law. This would still leave at least 20 GW of wind projects on track for construction. In the end, the head of Greece’s energy regulator, RAE, Athanasios Dagoumas, estimates around 10% to 20% of all wind and solar applications (currently exceeding a whopping 100 GW) will be built.

Location, location, location

The question, of course, is by which criteria the selection is determined. Even if only 10%-20% of applications lead to construction, it makes an enormous difference where this construction takes place. Without any way to set priorities, the current system essentially operates on a “first come, first served” basis. From an environmental standpoint, this means that valuable habitats could be damaged while there are less sensitive locations available.

The environmental viability of a project needs to be determined at the earliest possible stage, before any construction starts. Even if a project stops midway, after new roads have been opened, the damage to biodiversity is already done.

There is broad agreement that the current system doesn’t work. If land use in Greece is a black hole, then land use rules for renewables are a black hole within a black hole. The conservative government led by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has turned down the request of 9 environmental NGOs for a moratorium in new construction of wind parks and other large infrastructure in Natura 2000 areas (already, 190 parks with 700 turbines are operating in these protected areas). The government has, however, initiated a review of the vague and outdated rules that allowed companies to prioritise investment in the most pristine areas of the global biodiversity hotspot that is Greece. Will the new rules be any better? Will they come soon enough?

“Wind power is by definition friendly to the environment,” says Papastamatiou. “We do not build nuclear plants, we do not drill, we have zero carbon footprint”.

In the University of Ioannina, situated amongst some of the most impressive mountains of Greece, Professor of Biodiversity Conservation and Head of Biodiversity Conservation Lab, Vassiliki Kati, sees things differently.

Kati has spent decades studying Greece’s wildlife and she has seen the detrimental effects of road construction on species such as the Balkan chamois. Each wind farm in the middle of nowhere requires several kilometres of new roads, leading to fragmentation of valuable ecosystems, increasing artificial surfaces and facilitating other damaging activities, such as illegal hunting, logging and construction. Unlike most of northern Europe, Greece still has expansive roadless areas but fragmentation of the greek landscape proceeds faster than the european average.

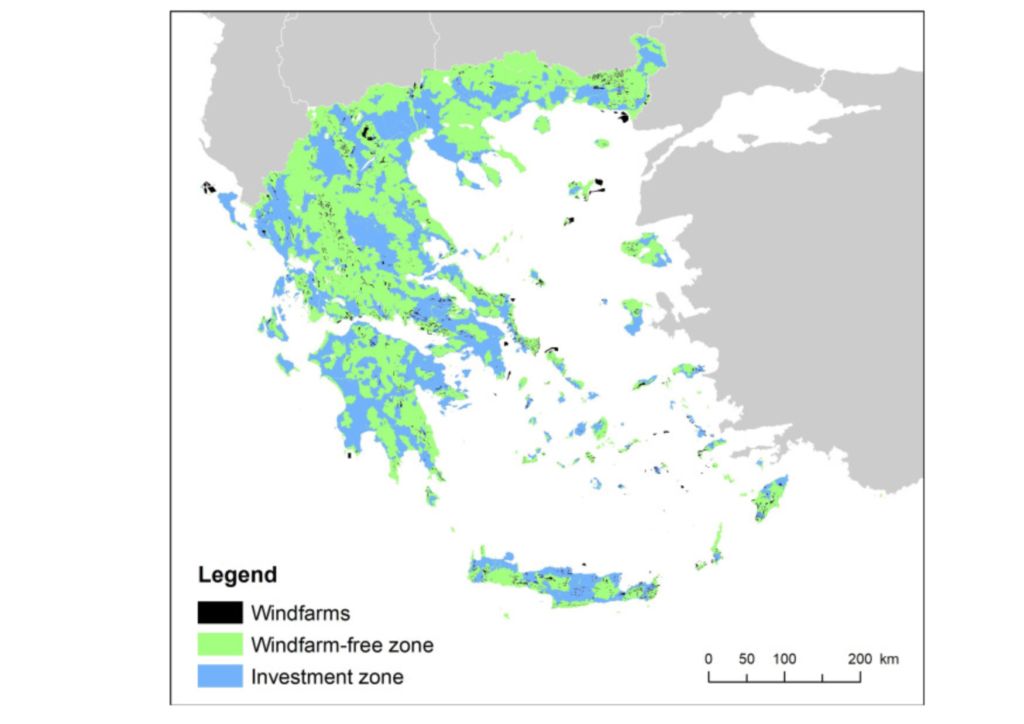

“We have two equally important imperatives, stopping climate change and arresting the biodiversity decline. We need more convergence between these two goals” says Kati. Her team recently suggested a concrete way to reconcile the two. In a peer-reviewed paper for the journal Science of the Total Environment she proposed an exclusion zone of ecologically sensitive areas, comprising 58,6% of the country, where no wind farms are allowed, leaving the rest as a potential investment zone.

Instead of a case-by-case appraisal of applications, as demanded by wind power companies, Kati proposes a horizontal rule. There is ample evidence documenting the mortal threats to biodiversity posed by land use change and habitat fragmentation. Plus, according to Kati, rules protecting entire ecosystems are better suited to addressing cumulative effects, which are underestimated if each wind farm is assessed independently. Adopting a horizontal rule would make the process more efficient for investors too, as it would mean they would not waste time, effort and money applying for wind turbines in areas protected by the Natura 2000 network of the EU, or in roadless and less fragmented areas.

Around 6 million data points from wind masts all over Greece show only 4% higher wind speeds on high mountains and other areas in the proposed exclusion zone than in the proposed investment zone. Wind speed is only one indicator when choosing appropriate locations, but what the 4% number shows is that the wind potential inside the investment zone should not be dismissed as inadequate.

Could this average value be misleading? Probably not. One can only assume wind companies have measured location-specific wind conditions before applying for permits, otherwise the plans would make no business sense. By this calculation, there are enough applications in the investment zone proposed by Kati to shift Greece to 100% clean energy.

How much wind power do we need?

Specifically, as of March 2020, before the massive recent rounds of applications, there were already applications for 10.7 GW of wind power in the investment zone. According to the National Long-Term Energy Strategy (LTS-2050, available in Greek here) Greece has submitted to the EU, fully covering Greece’s energy needs with clean energy would require an extra 8.9 GW of wind power from the current starting point (4.2 GW existing, 8.4 GW new terrestrial, 0.5GW offshore) of installed wind power by 2050 – or by 2040, if the government chooses to bring forward this goal, as environmental organisations suggest it should.

Needless to say, applications in the investment zone submitted by March 2020 were also overshooting the current modest national target for 2030 (total installed capacity 7 GW of wind power), as well as the stricter revisions of the 2030 target, expected this fall in order to bring Greece in line with the EU’S “Fit for 55” targets. “Suggesting an investment zone doesn’t delay wind power roll-out” says Kati “it is a win-win proposition.”

This is not quite true. There are two losers from these calculations, which is why the wind power industry is keen to reject the proposal. One is the vision of Greece as a clean energy “hub”, touted by wind-power executives (for example by the head of GEK Terna, in Greek here) and by Mitsotakis himself (in 2019 the soon-to-be prime minister called for Greece to become “The battery of Europe”). This relates to a notion whereby Greece systematically generates and stores excess electricity from renewable sources like wind with a view to exporting it. The second is the idea that green transition is tied to the development and subsequent massive deployment of “middleman fuels”, like hydrogen and yet-to-be invented synthetic fuels. Neither of these notions is essential for Greece to meet its climate goals.

Inside Greece, Kati’s proposal has been dismissed as leading to less wind power generation than the amounts necessary for a zero-emissions economy. But here is the catch. These amounts are not fixed, but rather depend on policy choices. The maximalist scenario in the Long Term Strategy (in terms of its requirement for renewables) is the one dubbed “New Carriers 1.5”, which relies heavily on the use of renewables to generate “green” hydrogen and other “middleman” fuels, rather than direct electrification using more proven – and more efficient – technologies like batteries and pumped storage. This doubles the amount of installed wind power required to cover demand.

The alternative “Efficiency & Electrification 1.5” scenario outlined in the Long-Term Strategy, in which renewable power is used for direct electrification, estimates that Greece needs an extra 8.9 GW of wind and 11 GW of solar power in order to cover the most stringent 2050 goals. Wind projects that have received a production permit as of 2021 cover the 2050 target for wind power more than three times over.

Reconciling biodiversity and climate protection

More than unfettered access to every mountain peak and every wind-swept island in the country, investors prize certainty. They wish to know in which areas it will be permitted to place wind farms and in which areas it will not. When – and if – the current, vaguely regulated free-for-all comes to an end and rules are put in place, what should these rules look like? What are the guidelines that would make wind energy not only renewable but also sustainable?

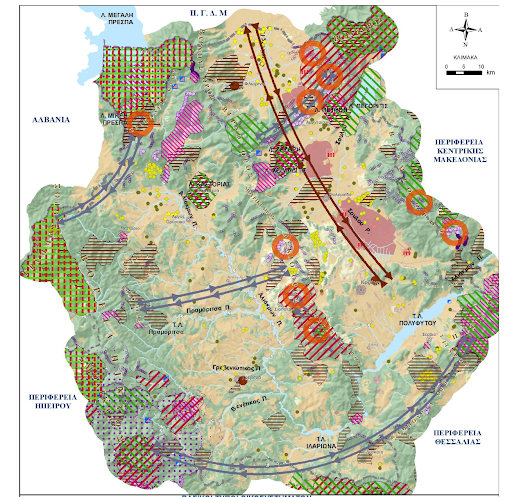

Lazaros Georgiadis, a biologist from Florina, North Western Greece and co-author of a recent report on “Biodiversity in the Balkan Peninsula”, suggests that no wind farm should be built without a proper impact assessment, determining that the impacts are reversible. “If a wind farm causes irreversible biodiversity loss, then it fails the sustainability criterion and it should not be built”, he says, cautioning that biodiversity is unrelated to the mass of the animal, meaning small grasshoppers or butterflies are just as valuable as large bears. It is imperative that maps pointing out sensitive areas for biodiversity and overlays with planned wind farms are drawn for the entire country. One region, Western Macedonia, already has such a map. It looks like this:

The conflict points are easy to spot: they are the orange circles, showing wind farms planned inside sensitive areas. What this map reveals is that sensitive areas are not only those included in the Natura 2000 network of protected areas (green and red stripes) but also the corridors connecting these protected areas. “Animals do not live in glass jars, they move around.” says Georgiadis. There are two types of corridors, one on land (grey color) and one in the sky (bird migration route, brown color). These should be respected – but currently they are not.

At the far north of the area depicted on the map, right at the intersection of a bird migration route and an ecological land corridor used by bears and other animals, lies Nymphaio, the gem of local mountain tourism. In June 2021, the environment ministry gave the go-ahead for a wind farm at this spot (not marked by an orange circle because the map uses 2015 data for wind farm applications, missing many of the most recent ones).

The Nymphaio project was approved, inviting a lawsuit by environmental organisations, just a few days after the Environment Ministry stopped in its tracks the application for a mega wind project on 23 islets of the Aegean, pointing out that the islands’ rich bird habitats could be irreversibly damaged (see RUs report on the “Mediterranean Galapagos”). “There is a war going on, we may win some battles, but the war is everywhere”, says Georgiadis, pondering the cascade of applications for wind farms all over Greece’s mountaintops. Georgiadis has his own suggestions.

He believes a National Master Plan for Renewable Energy should be created, to underpin the permitting process by setting priorities at a strategic level. Georgiadis also argues that Special Area Plans should be drawn up for each region, while the impacts of wind farms already in place should be properly monitored, paying special attention to the cumulative nature of the effects on biodiversity. It is also necessary in his view to engage the stakeholders, abide by the law (no cutting corners under the guise of “fast-tracking”) and, finally, going beyond biodiversity, the planning system should take landscape into account, preserving areas of exceptional natural beauty.

A Νational Αrea Plan for renewable Energy and several Special Area Plans for many regions are now being drafted, but there is a huge question mark as to whether there are enough resources devoted in this process to make them fit for purpose. The contract for evaluating the old National Area Plan for Renewable Energy Sources (RES) and drafting the new one is costed at 130,000 euros (in Greek here), a very small amount for a project of this scope and scale. Two years on, the plan is still being drafted, while another project, aiming to finally pinpoint the exact coordinates of the already existing exclusion areas (archaeological sites etc.) is costed at 186,000 euros (in Greek, here), again a paltry sum given the absence of precise data for large swaths of the Greek territory.

It is in the knowledge of these gaps that Kati proposed a priori excluding 58.6% of the Greek territory from new wind farm development, since most sensitive areas do in fact fall within this 58.6% of Natura 2000 sites and least fragmented territories.

Most importantly, critics of the government’s approach point out that a plan regulating land use for renewable energy (which will eventually be in place, however incomplete) is not the same as a National Master plan for Energy Transition. Such a Master Plan would take into account the country’s total energy needs, potential for savings through efficiency and goals for lowering emissions. It could outline alternative scenarios, answering the following question: how much wind power is really necessary for the transition to zero emissions and to what extent the transition can be accomplished through RES already in place and through new production located on artificial surfaces, rather than unspoilt natural features. Such installations are already foreseen, both at utility scale – such as those planned for the former lignite mines in Northern Greece and the Peloponnese – and smaller, decentralized plants and rooftop installations. Prioritising such schemes over virgin installations could substantially reduce the need to venture close to sensitive ecosystems and pristine mountaintops.

The first question should not be where it would be optimal to place wind turbines in Greece’s mountains, but how many are really needed, after the potential for energy efficiency, for less invasive installations for solar and wind power in locations already altered by human intervention, for hydropower and geothermal generation, is exhausted.

Kati’s approach shows there is ample space for the Greek government to both lead Greece to 100% renewable energy and protect its most valuable habitats. All it needs to do is let go of the idea of Greece as a green energy “hub”. It also needs to focus on the realistic scenario of energy efficiency and electrification, rather than on a highly speculative hydrogen-plus-new-fuels-powered future. There is no need to clip wind power investors’ wings, just to bring their profit motive in line with the preservation of Greece’s biodiversity and pristine beauty.

A shorter version of this article was published in German by the NZZ.