Data visualisation by Sotiris Sideris

Map by Mauricio Reyes Cardoso / Global Fishing Watch

Editing for English by Georgia Nakou

“On March 31 they put out the buoys, brought in the cranes, they dredged and dumped. Every day until late into the night, and sometimes through the night, they were digging, filling barges and dumping the contents between [the islands of] Aegina and Salamis”.

Paediatrician and Piraeus city council member Dimitra Vini watched the work taking place during Greece’s first pandemic lockdown in spring 2020 with some trepidation. The location she describes is the Port of Piraeus where Chinese logistics giant COSCO, which has owned a controlling stake in the Piraeus Port Authority (PPA) since 2016, has started work on a cruise ship pier. The first phase of the project would allow two cruise ships to dock, while in its final form the port should be able to accommodate six 350-metre cruise ships.

COSCO initially took over the container operations of Piraeus port in 2009 with a 35-year concession and the goal to develop the port into a logistics center to move goods towards Europe. In 2016, it bought a 51% stake in Piraeus Port Authority for 280 million euros under the first phase of a concession agreement that will expire in 2052, also providing that COSCO would gain another 16% by summer of 2021, should it complete eleven mandatory investments worth 294 million euros. The first phase of the extension of the cruise ship pier was one of these investments.

Source: Paratiritirio Piraïkis- Peiraia (Piraeus Port Environmental Observatory)

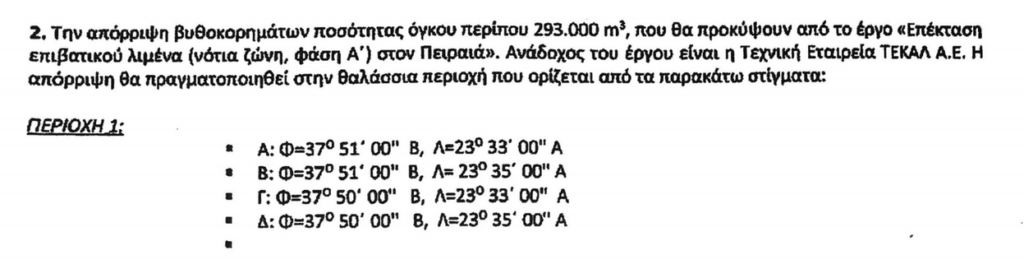

Deepening the port to accommodate the massive hulls involves dredging the seabed where the waste of decades of activity in Greece’s main commercial port has settled. We now know that the sludge in the barges which Vini witnessed probably constitutes most of the 293,000 cubic meters of mud which COSCO was given permission by the Greek authorities to dispose of at sea.

The chemical analysis submitted as part of the licensing application found that the mud from the seabed contained high concentrations of mercury and other heavy metals, at levels harmful to public health. Τhe COSCO-owned PPA, however, had been dumping it at sea with the blessings of the relevant Greek authorities – the Environment Ministry, the Ministry of Shipping, the Decentralised Administration of Attica and the Central Coastguard of Piraeus.

Worse still, the coordinates set out in the environmental license for the disposal define an area in the middle of the Saronic Gulf which is crisscrossed daily by fishing boats, supplying the markets and restaurants of Athens and the islands with fish and seafood.

Citizens of Piraeus who were not happy with the environmental terms of the project, as well as with other projects in the port, have appealed to the Council of State, the Greek supreme administrative court. A decision by the court is due shortly.

“Absolutely no pollution issues”

PPA was granted a license by the Coastguard to dispose of the mud dredged from the harbour on 11 March 2020 on the basis of chemical analysis of the sediments from the harbour floor.

Reporters United has seen the January 2018 technical report on the results of the chemical analysis, which was produced by the Laboratory of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry of the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) under Emeritus Professor Aggeliki Moutsatsou. The report (which can be found here in Greek) concludes that “disposal of (the dredged materials) is possible with absolutely no pollution issues”.

Other experts that Reporters United has spoken to, however, claim that the concentrations of heavy metals found in the sediment exceed the toxicity limits set in international standards. Biochemist Vassilios Tselentis is Professor of Marine Environment and head of the Laboratory of Marine Sciences at the University of Piraeus. His own study of the chemical analysis shows that concentrations of chromium, nickel, zinc, arsenic, cadmium, mercury and lead in many cases exceed ERM (effect-range median) limits set out in international standards – the values above which they are known to cause irreversible damage to 65% of marine organisms.

Reporters United also showed the results to Michalis Leotsinidis, a chemist, Professor of Hygiene and Director of the Laboratory of Hygiene at Patra University. Professor Leotsinidis explains, “the TEL (threshold effect level) of mercury – one of the indices used to determine safety limits – is 0.13 mg/kg according to the standards used in Florida. At 6 mg/kg, the concentrations found in Piraeus are 46 times the limit”.

Danger to public health

Professor Vassilios Kapsimalis is head of research at the Oceanography Institute of the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR), the state agency tasked with monitoring water quality. The HCMR advised the Greek Environment Ministry to introduce a program of environmental monitoring of the disposal area. Until then, it suggested that the ministry should “consider limiting fishing activities with slider fishing nets in the specific location’ (where the dredging spoil was disposed of). Reporters United asked Professor Kapsimalis why HCMR made this recommendation. He explained that fish and shellfish concentrate mercury in their bodies, a process known as bioaccumulation.

“If these metals are able to escape from the seabed and become suspended once again, they could enter the food chain. From one link of the food chain to the other, they bioaccumulate, so that even if they are found in low concentrations in the water, for example 1 mg/lt, they can reach 1,000 mg/kg as they accumulate between the plankton and the fish”.

Such levels can cause mercury poisoning in marine organisms and the humans who consume them and cause permanent serious damage to the central nervous system.

Kapsimalis adds that for this reason the London and Barcelona Protocols for the protection of the sea recommend avoiding the disposal of the products of dredging in areas with intensive fishing activity.

According to the Panhellenic Association of Public Sector Ichthyologists, the area of Piraeus and the surrounding islands is exploited by around 750 commercial fishing vessels, while it is also home to 20 fish farms and 16 fish processing and wholesale businesses which supply not only the greater Athens area but many parts of the country.

“This”, according to Professor Leotsinidis, “raises serious issues for those who carried out the analysis and granted the disposal license”.

A license to pollute?

Reporters United asked the Environment Ministry why the chemical analysis carried out by NTUA was able to give COSCO the green light to dispose of toxic sludge in some of Greece’s busiest fishing waters.

The Ministry directed us to the Joint Ministerial Decision of May 2006, which set out the terms of the original environmental license for the Piraeus Port Master Plan, while the PPA was still under Greek state control. The document (available here in Greek) makes the PPA responsible for commissioning the chemical analysis and specifies the methodology to be applied (the full response from the Ministry for the Environment is available here in Greek).

The license specifies the use of leachability testing, which essentially involves bringing solid samples (e.g. soil) in contact with water to determine what contaminants are released. This is the method used in the NTUA study which cleared the sludge for disposal, and by other studies of the Piraeus sediments commissioned since 2006. There are, however, known problems with this approach.

Biochemist Vassilios Tselentis raised the issue in a report dated June 16, 2020 (available here in Greek), in which he explained why leachability testing is not recommended in relation to disposing of solid waste at sea:

“Compared to other criteria or international standards, the concentration of heavy metals in the sediments examined by NTUA were many times over safe limits. The leachability testing allows them to state that there are heavy metals present, but that they do not leach out. This is wrong, because leaching is not the only mechanism by which they can be released in the marine environment. Microorganisms can metabolise the material in the seabed and release toxic substances this way”.

This method was selected based on EU Council Decision 2003/33/EC. According to sources at the Environment Ministry who spoke on background, this was the only way for the authorities to be able to provide for criteria, as to whether the dredges are hazardous or not. This decision, however, applies to the disposal of waste through burial on dry land, not disposal at sea.

The same ministry sources also told Reporters United that the Greek state should already have set national limits or standards for the concentration of heavy metals in dredging spoils, based on which it could be determined whether they can be disposed of at sea. This has not happened to this date.

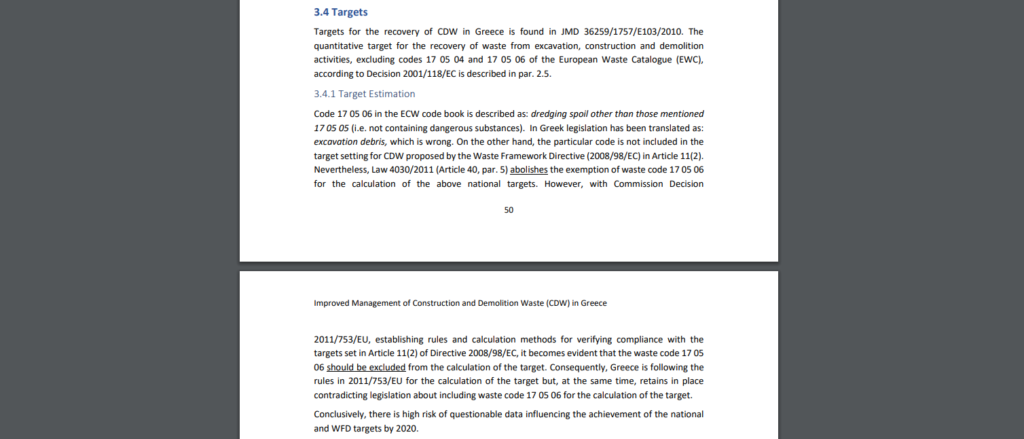

In fact, the problem with treating dredging spoils in Greece goes deeper, and dates back at least twenty years.

Lost in translation

Reporters United also found that Greek law has no separate designation for dredging spoils. This is due to a sloppy transposition of the European Waste Catalogue, the typology which has determined since 2000 which materials are treated as hazardous waste according to EU legislation. As the German International Development Agency GIZ pointed out in a report to the Greek government in August 2020, the Greek translation misclassifies dredging spoils as “excavation debris”.

In practical terms, this means that dredging spoils are not treated as potentially hazardous waste, and can be disposed of following a general rule at a depth of 50 metres just one nautical mile from the shoreline.

According to Haris Mourkakos, director of the southern Greek chapter of Greece’s construction waste management agency AANEL, this misclassification could potentially affect the treatment of around 2.5 million tonnes of waste annually.

A different testing methodology could reject disposal at sea for the Piraeus sediments in favour of other, potentially more costly, options, which could add to the expense of the project for COSCO. However, HCMR and other experts, along with environmentalists and local activists, are concerned that the current methodology has already cost the environment dear.

The real risks

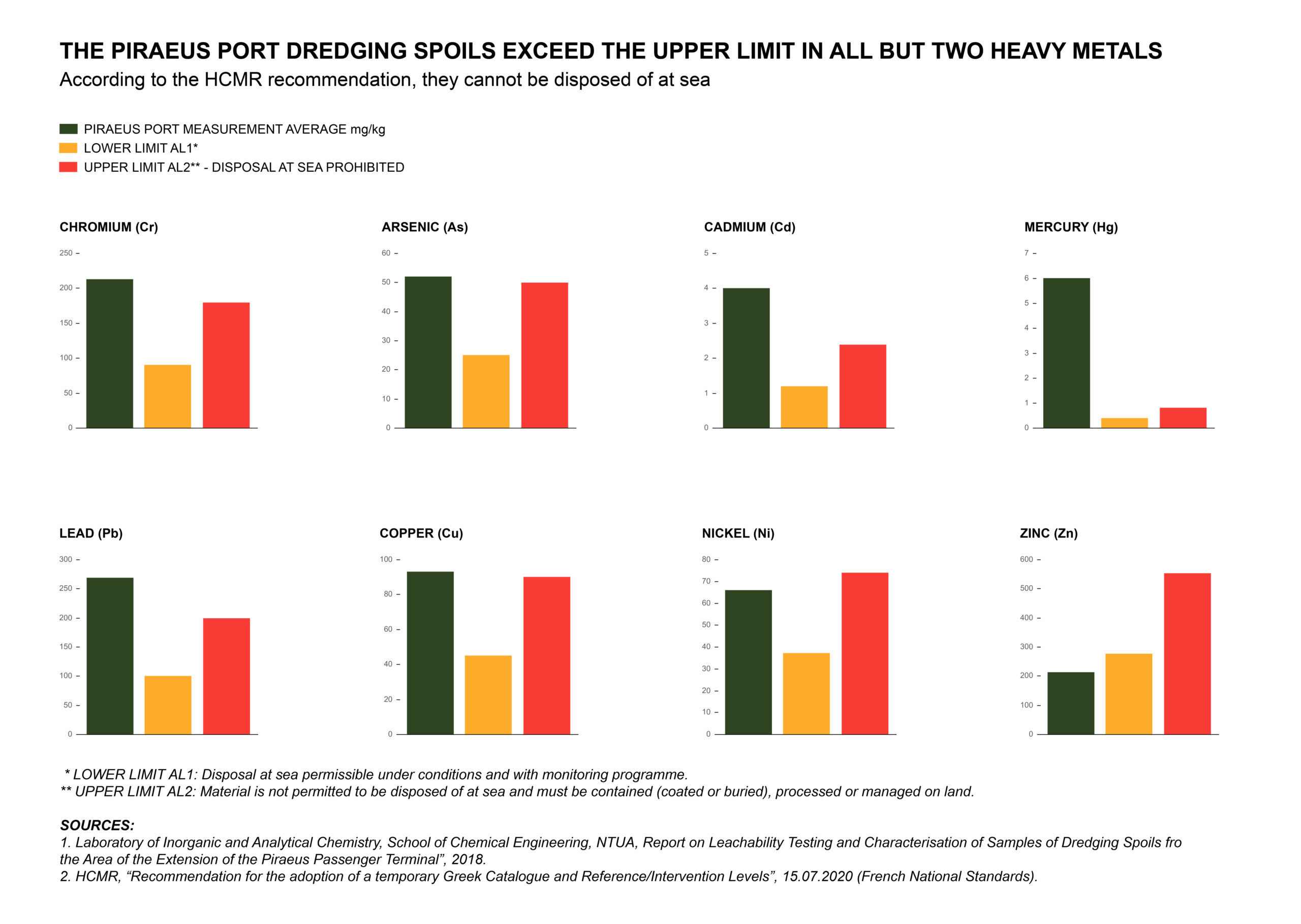

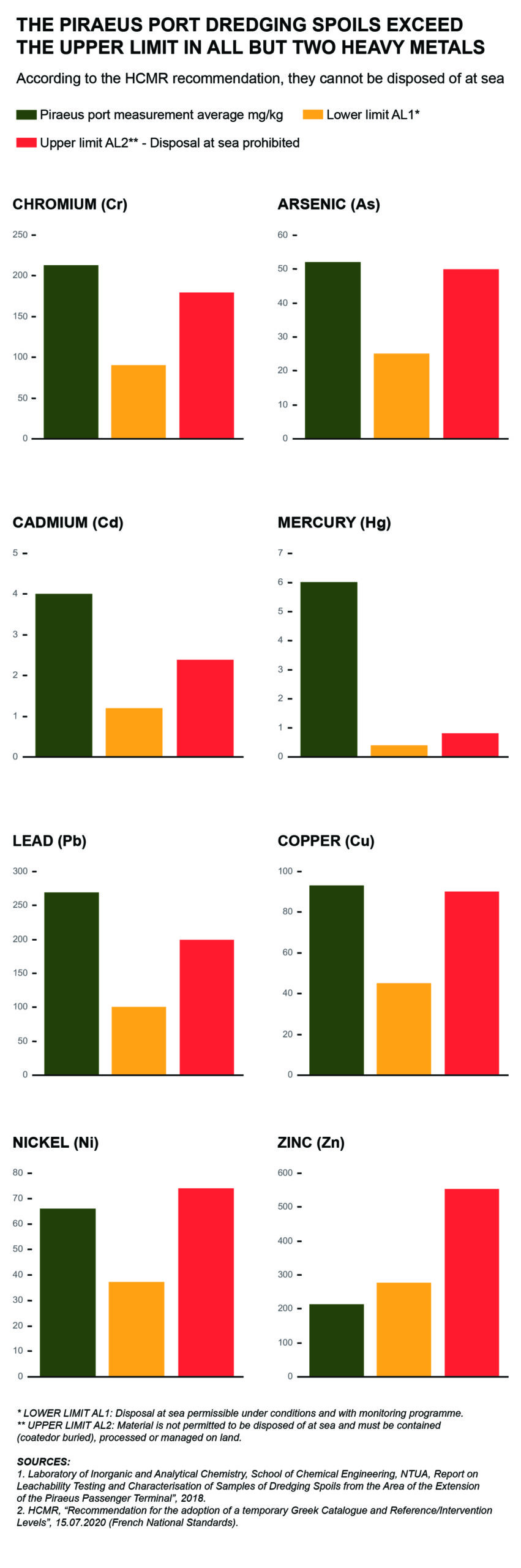

In an opinion paper and annex requested by the Environment Ministry in order to revise regulations for sea dredges in Piraeus, HCMR has recommended that the ministry adopt temporary standards for heavy metal concentrations for waste disposal at sea, based on those used by France and Italy, while waiting for permanent standards to be set.

Data Visualization: Sotiris Sideris

Data Visualization: Sotiris Sideris

The chemical concentrations of the sea dredges excavated from Piraeus exceed these limits in six out of eight heavy metals that the HCMR and other experts recommend to be measured, citing the Dumping Protocol of the Barcelona Convention: chromium, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, lead and copper. A seventh, nickel, appears in concentrations between the middle and upper limit. Only zinc appears within safe limits. According to the HCMR, when “the concentration of one of the pollutants exceeds AL2 limits, the material must not be disposed of at sea, and must be subjected to containment (burial or covering), processing or management on land”.

Comparing the findings with other international standards – for example those used in the Netherlands – leads to similar results. Heavy metal concentrations in the samples exceed the limits for dangerous waste.

In the minutes of an earlier discussion on the treatment of dredging spoil with the Piraeus Port regulator, which has since been abolished, Professor Kapsimalis summarised the situation created by the gaps in legislation (the minutes are available here in Greek):

“We who analyse the chemical composition of dredging spoils see ridiculously high readings by scientific standards, I mean sky-high. At the same time, someone who has undertaken their disposal can tell us that the material is not hazardous based on Greek legislation, because there are no legally defined pollution limits”. He goes on to say, “If the materials are not clean, there is a procedure which must be followed, and this is set out in detail in published guidelines specifically for Mediterranean countries. Everyone uses them except Greece. We are guided by legislation enacted in 1978-79 and nothing more. In scientific terms, we are a laughing stock”.

No consultation

There are other problems with the way the disposal permit was granted, too.

Reporters United obtained from the Environment Ministry the Environmental Impact Study (available here in Greek) submitted by the PPA in 2011 in support of its original application for extension of Piraeus harbour including the building of the cruise terminal.

The study has several problematic areas, not least of which it relies on chemical analysis of sediment from a different area of the harbour than the proposed site of the cruise terminal. It also grossly underestimates the amount of waste expected to come from the dredging – just 10,000 cubic metres compared to the 300,000 cubic metres in the disposal license.

This Environmental study was also omitted from the legally required public consultation process, which took place in 2012 prior to the granting of the original permission for the harbour extension in 2013. This information, along with other supporting evidence, was transferred from the ministry to the Decentralised Administration of Attica in 2018, marked for publication “with no requirement for consultation”.

The only time that the NTUA study with the actual results from the dredges of the cruise port excavation was included in a public consultation was when the PPA (by this time controlled by COSCO) submitted an updated Environmental Impact Study in 2019 in order to renew the environmental license for the port redevelopment Master Plan. At this point, the cruise pier had already been approved.

It turns out this is not the first time that dredging spoils were disposed of by COSCO-PPA in the same patch of sea. In 2016 the Environment Ministry licensed the disposal of 100,000 cubic metres of dredging spoils from the construction of Pier III. The same NTUA lab had carried out the analysis using the same methodology, and gave the same verdict: the material could be disposed of at sea “without causing any pollution issues” (the report is available here in Greek).

The chemical analysis showed toxic levels of chromium, nickel, copper and zinc according to international standards.

After the event

After examining legal challenges mounted by two separate citizens’ groups, the Council of State, Greece’s highest administrative court, halted the dredging activities on June 11. However, in the intervening weeks it appears that most of the damage was already done.

In December 2020, after the Council of State halted the dredging, the Environment Ministry published updated environmental terms for the project, in which it adopts the HCMS’s recommendation to “harmonise” the NTUA study with international limits, and requires the PPA to submit a new technical study, potentially requiring additional analyses of the harbour sediment. The new terms (available here in Greek) also recommend a two-year programme of environmental monitoring as recommended by the HCMS.

The HCMS had also recommended a freeze on fishing in the area during the monitoring period. This was not endorsed by the ministry.

The ministry also rejects the HCMS recommendation to adopt temporary concentration limits for heavy metals, which are based on the national limits of France for heavy metals. When Reporters United asked why, the ministry responded that “the adoption of nationally-applicable measures is not possible in the context of granting an environmental license for a specific project”, claiming that they chose to apply the guidelines on the management of waste set out in the Barcelona Convention. The reply of the Ministry can be found, in Greek, here.

The Barcelona convention does not endorse any country limits, but refers to the national limits used by France, Italy and Spain. A comparison with the limits of Italy and Spain shows that the waste deposited in the Saronic gulf clearly exceeds the limits for between 4 and 7 of the 8 elements measured.

However, the damage has already been done, as it appears that most of the dredging waste was already disposed of by the time the work was stopped.

Exactly how much material was disposed of is hard to establish. PPA has avoided giving a direct response (twice) to the question sent by Reporters United (full correspondence is available here in Greek). The Central Coastguard of Piraeus, who issued the final approval for the disposal, also avoided answering our question, and so has the Environment Ministry.

However, a source at the ministry told Reporters United that the contractor had already disposed of around 70% of the dredged material.

In addition, Anthi Giannoulou, a Piraeus lawyer who has represented the citizens in one of the appeals made at the Council of State, has gathered evidence from eyewitnesses suggesting that the dredging continued illegally after the court order was issued.

Video by Konstantinos Stathias.

The Council of State is due to issue a final decision on dredging and other environmental objections concerning the port investments shortly. If it rejects the appeals by the citizens of Piraeus, it will give leeway to PPA to complete the investment of the cruise ship pier, already facilitated by a recent amendment to the concession agreement with COSCO, which provided a five to ten years extension period.

The cruise ship pier was one of the so-called mandatory investments that COSCO had to conclude by this summer in order to gain another 16% stake of Piraeus Port Authority. Having failed to do so, this fall the Chinese state company was granted the stake anyway,

for 88 million euros plus 11.87 million euros in accrued interest and a letter of guarantee of 29 million, after legislation which amended the initial concession agreement was passed this September.

The Greek legislators who voted for the amended agreement, putting it into law (the draft text of which is available here in Greek), in fact accepted COSCO’s reasoning that the delays were due to factors “beyond reasonable control of the PPA”. This seems to be implying that the court appeals are disconnected from and irrelevant to the environmental decisions made by the PPA and its contractors.